“Shark!” When you hear this word, especially at the beach, it can conjure up images of bloodthirsty monsters. This summer – particularly on July 14, which is Shark Awareness Day – my colleagues and I are eager to help the public learn more about these misunderstood, ecologically important and highly threatened animals and their close relatives – rays and chimaeras.

As a marine biologist focused on conserving sharks, I want people to know that an estimated one-third of them are at risk of extinction. Second, there’s an amazing variety of species in an astounding variety of shapes sizes and colors, and many of them get very little attention.

Here is an introduction to a group of fishes that are at extremely high risk of extinction, and also delightfully weird: the rhino rays, named for their elongated noses.

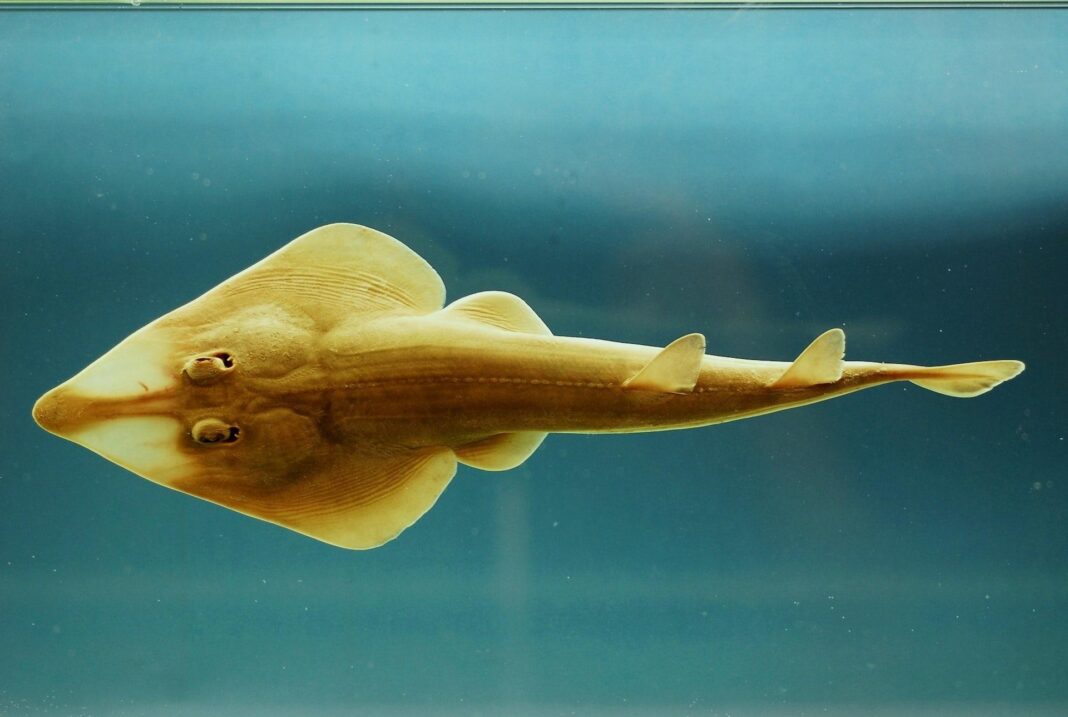

Rhino rays are sharklike rays from five families: sawfish, wedgefish, giant guitarfish, guitarfish and banjo rays. The sawfish has a chainsaw-like extension in front of its mouth that it uses to stun and shred its prey. Banjo rays and guitarfishes have body shapes that resemble those respective musical instruments. Wedgefishes are, well, wedge-shaped, like doorstops with fins and tails.

These fishes are found in tropical and warm temperate waters all over the world, but many species have extremely restricted ranges. For example, the false shark ray (Rhynchorhina mauritaniensis) is known to inhabit only one bay, on the coastline of Mauritania.

Rhino rays range in size, from 2 to 3 feet long (less than 1 meter) at one extreme to the largest species, the green sawfish (Pristis zijsron), which can grow to 23 feet (7 meters). They all are carnivores and eat all kinds of things, but mainly small crustaceans and fish, as well as worms that live in sand or mud. All rhino rays give birth to live young, just as mammals do.

Sometimes rhino rays’ unusual features cause them problems. For example, fishing boats often haul in smalltooth sawfish (Pristis pectinata) as bycatch, or accidental catch, because their saws become tangled in fishing gear. Currently, shrimp trawl nets pose a serious threat to this species.

The smalltooth sawfish was the first marine fish species listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, in 2003. Once found from North Carolina to Texas, it now is restricted to small parts of south Florida, a range reduction of more than 95%. In some parts of the world, populations are starting to recover, but local extinction of sawfish from countries where they were once so common that they’re featured on currency has earned them the nickname “Ghosts of the Coast.”

Another rhino ray, the bowmouth guitarfish (Rhina ancylostomus), can grow up to 10 feet (3 meters) and has thornlike ridges covering its head and back. A recent study reported that these thorns are actively traded online among buyers who believe the thorns contain magical properties and use them to make protective amulets. While overfishing for fins and meat is the most serious threat to sharks and rays overall, it also is important to consider these kinds of niche threats to some species.

Fortunately, there are conservation solutions that can be used to protect these animals and their important habitats. To reduce bycatch, some solutions require changing fishing gear.

“For gill nets, simple measures like lifting the net off the seafloor so sawfish have space to swim under them without getting tangled can help,” Charles Darwin University biologist Peter Kyne told me in an interview. Using lights to illuminate nets has drastically reduced bycatch in some places. Kyne and his colleagues are testing devices that generate electric fields underwater to make sawfish swim away from nets so they don’t get entangled.

When bycatch can’t be averted, another strategy is training fishers to safely handle and release nontargeted species so that the fishes survive the encounter. Release-based conservation initiatives are an opportunity for scientists to collaborate with fishing communities and the public.

“For sawfishes, we started conservation work when species had already disappeared from across their historical range. We now have an opportunity to save the remaining species of rhino rays before it’s too late,” Rima Jabado, chair of the Shark Specialist Group for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Species Survival Commission, told me in an interview. “We know that fishing is the primary threat, and we have solutions to minimize bycatch.”

To learn more about rhino rays, follow #SharkAwarenessDay (July 14) and #RhinoRay on Twitter and Instagram for posts from scientists, conservation experts, government agencies, zoos and aquariums all over the world. You can find the IUCN Species Survival Commission Shark Specialist Group on Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn for weekly updates about the conservation status of these amazing and threatened animals.

Rima Jabado, chair of the IUCN Species Survival Commission Shark Specialist Group (SSG), contributed to this article.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. If you found it interesting, you could subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Read more: Beware of ‘Shark Week’: Scientists watched 202 episodes and found them filled with junk science, misinformation and white male ‘experts’ named Mike Is there life in the sea that hasn’t been discovered?

David Shiffman currently serves as the communications officer for the IUCN Species Survival Commission Shark Specialist Group