The state of Florida ignited a controversy when it released a set of 2023 academic standards that require fifth graders to be taught that enslaved Black people in the U.S. “developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their benefit.”

As a researcher specializing in the history of race and racism in the U.S., I – like a growing chorus of critics – see that education standard as flawed and misleading.

Whereas Florida would have students believe that enslaved Black people “benefited” by developing skills during slavery, the reality is that enslaved Africans contributed to the nation’s social, cultural and economic well-being by using skills they had already developed before captivity. What follows are examples of the skills the Africans brought with them as they entered the Americas as enslaved:

During the period between 1750 and 1775, the majority of the enslaved Africans that landed in the Carolinas came from the traditional rice-growing regions in Africa known as the Rice Coast.

Subsequently, rice joined cotton as one of the most profitable agricultural products, not only in North Carolina and South Carolina but in Virginia and Georgia as well.

Other African food staples, such as black rice, okra, black-eyed peas, yams, peanuts and watermelon, made their way into North America via slave ship cargoes.

Ship captains relied on African agricultural products to feed the 12 million enslaved Africans transported to the Americas through a brutal voyage known as the Middle Passage. In some cases the Africans stowed away food as they boarded the ships. These foods were essential for the enslaved to survive the harsh conditions of their trans-Atlantic trip in the hulls of ships.

Once on plantations in the land now known as the United States, enslaved people occasionally were able to cultivate small gardens. In these gardens, reflecting a small amount of freedom, enslaved men and women grew their own food. Some of the crops consisted of produce originating in Africa. From these they added unique ingredients, such as hot peppers, peanuts, okra and greens, to adapt West African stews into gumbo or jambalaya, which took rice, spices and heavily seasoned vegetables and meat. These dishes soon became staples in what would become known as down-home cooking. Crop surpluses from the communal gardens were sometimes sold in local markets, thus providing income that some enslaved people used to purchase freedom. Some of these African-derived crops became central to Southern cuisine.

The culinary skills that the West Africans brought with them served to enhance, transform and produce unique eating habits and culinary practices in the South. Although enslaved Africans were forced to cook for families that held them as property, they also cooked for themselves, typically using a large pot that they had been given for the purpose.

Using skills from various West African cultures, these cooks often worked together to prepare communal meals for their fellow enslaved people. The different cooking styles produced a range of popular meals centering on one-pot cooking to include stews or gumbos, or layering meat with greens. The meals comprised a high proportion of corn meal, animal fat and bits of meat or vegetables. Communal gardens, maintained by the enslaved, might supplement the meager supplies and what was available from hunting or fishing. Some of the cooks who emerged from these conditions became some of the highest regarded and valued among the enslaved in the regions.

Enslaved chefs blended African, Native American and European traditions to create unique Southern cuisines that featured roasted beef, veal, turkey, duck, fowl and ham. Desserts and puddings featured jellies, oranges, apples, nuts, figs and raisins. Stews and soups changed, given the season, sometimes featuring oysters or fish.

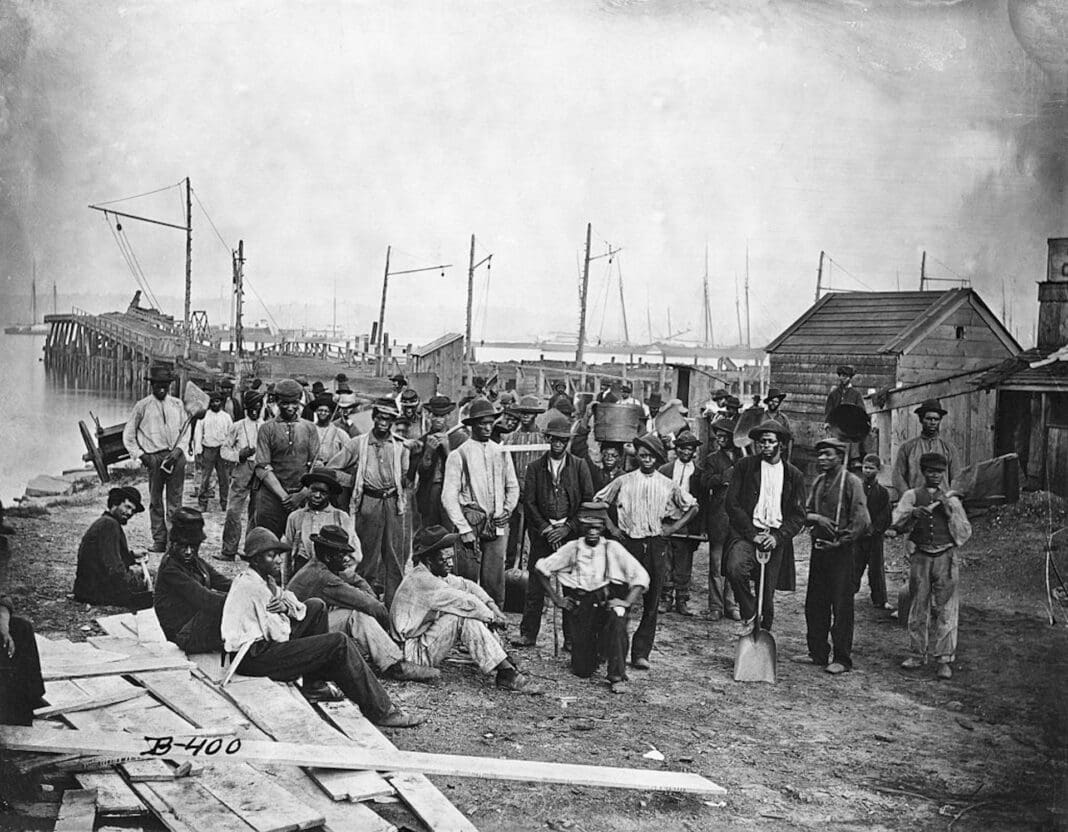

Slave ship manifests reveal that enslaved Africans included some who were woodcarvers and metalworkers. Others were skilled in various traditional crafts, including pottery making, weaving, basketry and wood carving. These crafts were instrumental in filling the perpetual scarcity of skilled labor on plantations.

When planters and traders considered purchasing an enslaved Black person, one of the key factors influencing their decision and the price was their skills. Slave auction sales included carpenters, blacksmiths and shoemakers.

Architectural designs showing West African influences have been identified in structures excavated from some colonial plantations in various areas of the South Carolina Lowcountry. These buildings, with clay-walled architecture, demonstrate that the West Africans came with building skills. Excavated clay pipes in the Chesapeake region reveal West African pottery decorative techniques.

Across the nation, multiple landmarks were built by the enslaved. These include the White House, the U.S. Capitol and the Smithsonian Castle in Washington, Fraunces Tavern and Wall Street in New York, and Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

As Africans entered the Americas, they brought knowledge of medicinal plants. Some enslaved women were midwives who used medical practices and skills from their native lands. In many cases, while many of these plants were unavailable in the Americas, enslaved Africans’ knowledge, and that gleaned from Native Americans, helped them to identify a range of plants that could be beneficial to treat a wide range of illnesses among both the enslaved and the enslavers. Enslaved midwives delivered babies and, in some cases, provided the means for either avoiding pregnancies or performing abortions. They also treated respiratory illnesses.

These practices and knowledge grew as they began incorporating techniques from Native American and European sources. They employed an interesting array of these practices to identify herbs, produce devices and to facilitate childbirth and maternal health and well-being. They utilized several herbal remedies such as cedar berries, tansy and cotton seeds to end pregnancies.

In 1721, of the 5,880 Bostonians who contracted smallpox, 844 died. Even more would have died had it not been for a radical technique introduced by an enslaved person named Onesimus, who is credited with helping a small portion of the population survive.

Onesimus, purchased by Cotton Mather in 1706, was being groomed to be a domestic servant. In 1716, Onesimus informed Mather that he had survived smallpox and no longer feared contagion. He described a practice known as variolation derived by West Africans to fight various infections.

This was a method of intentionally infecting an individual by rubbing pus from an infected person into an open wound. Onesimus explained how this treatment resulted in significantly milder symptoms, eliminating the likelihood of contracting the disease. As physicians began to wonder about this mysterious method to prevent smallpox, they developed the technique known as vaccinations. Smallpox today has been eradicated worldwide primarily because of the medical advice rendered by Onesimus.

Regardless of how Florida’s education standards misrepresent history, the reality is that the Africans forced to come to America brought an enormous range of skills. They were farmers, cooks, chefs, artisans, builders, midwives, herbalists and healers. Our country is richer because of their skills, techniques and knowledge.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. Like this article? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Read more: Politicians seek to control classroom discussions about slavery in the US 3 ways to improve education about slavery in the US

Rodney Coates does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.