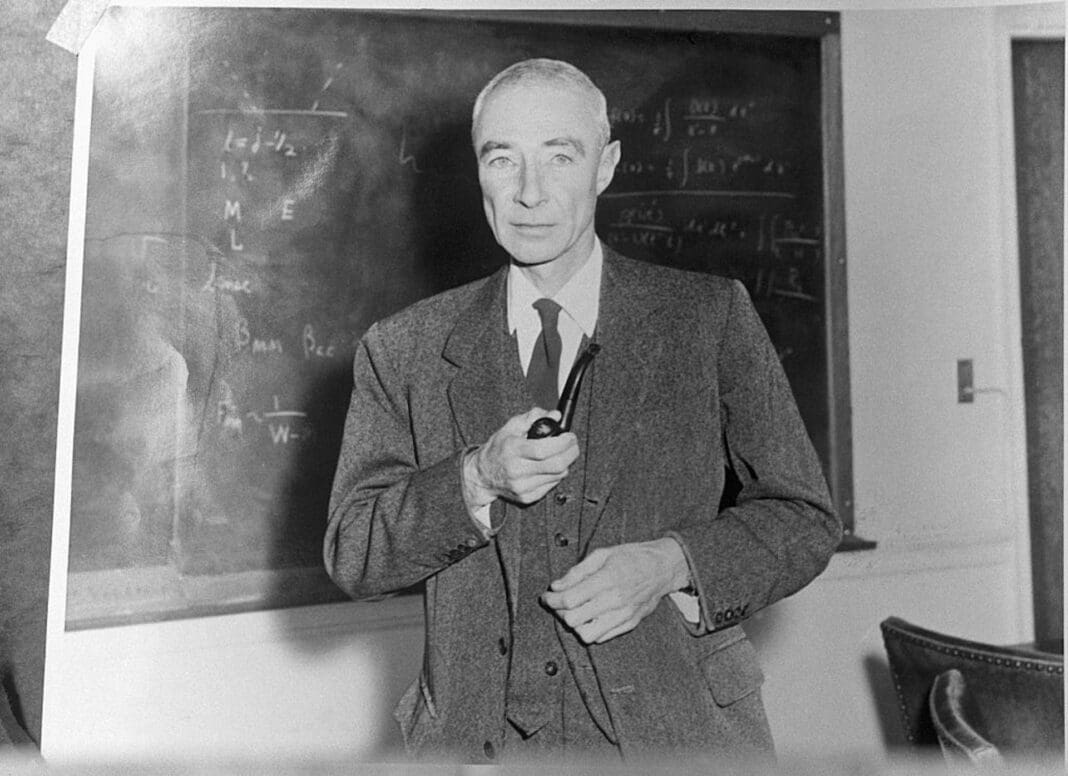

J. Robert Oppenheimer’s triumph was his tragedy. Oppenheimer had many achievements in theoretical physics but is remembered as the so-called father of the atomic bomb. Under his directorship, scientists at Los Alamos Laboratory, where the bomb was designed and built, forever changed how people view the world, adding a new sense of precariousness.

Oppenheimer’s life provides a human-scaled way to talk about an otherwise overwhelming topic. It’s little wonder that Christopher Nolan’s new film, “Oppenheimer,” tells the story of Los Alamos through this single life – or that Oppenheimer is the focus of so much writing about the bomb

In American culture, however, fascination with the man behind the bomb often seems to eclipse the horrific reality of nuclear weapons themselves – as if he were the welder’s glass allowing viewers to safely look at the explosion, even as it obscures the blinding light. Intense interest in Oppenheimer’s life and his ambivalent feelings about the bomb have turned him into almost a myth: a “tortured genius” or “tragic intellect” people try to comprehend because the terror of the bomb itself is too disturbing.

For the rest of his life, Oppenheimer gave the U.S. government’s justification of the atomic bombings: that they saved lives by preventing the need for invasion. But he conveyed a sense of anguish – scripting his own tragic role, as I argue in my book about him. “The physicists have known sin,” he remarked two years after the attacks, “and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”

The atomic bomb changed the meaning of the apocalypse. Where people had once pictured doomsday as an act of God’s wrath or final judgment, now a world could could be gone in an instant, with no sacred significance, no story of salvation. As physicist Isidor Isaac Rabi later said, the bomb “treated humans as matter,” nothing more.

But Oppenheimer pointedly used religious language when talking about the project, as if to underscore the weight of its significance.

The atomic bomb was first tested in the early morning of July 16, 1945, in the arid basin of southern New Mexico. Oppenheimer christened that test “Trinity,” referring to a sonnet by the English Renaissance writer John Donne, whose verses are famous for merging the sacred and the profane. “Batter my heart, three person’d God,” Donne pleads in “Holy Sonnet XIV,” asking God: “make me new.”

Later in life, Oppenheimer famously said that he had recalled words from the Bhagavad-Gita, a classical Hindu text, as he witnessed the sight and sound of the mushroom cloud: “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds” – lines that originally described the Lord Krishna revealing his full power. According to Oppenheimer’s brother Frank, however, a physicist who was with him at the time, what they both said aloud was simply, “It worked.”

The contrast between their accounts speaks to the duality in Oppenheimer’s public image: a technical expert forging a weapon, and a poetic humanist burdened by the bomb’s moral significance. As a spokesperson and symbol of the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer sometimes seemed to encourage the idea that it was his personal creation and responsibility. In fact, the bomb was the product of a gigantic scientific, engineering, industrial and military operation, one in which scientists sometimes felt like cogs in a machine. There really was no individual “father” of the atomic bomb.

Mathematician John von Neumann acerbically observed, “Some people profess guilt to claim credit for the sin.”

Only weeks after the test, atomic bombs flattened the previously bustling cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, these cities suddenly ceased to be. Robert J. Lifton, an expert on the psychology of war, violence and trauma, called the Hiroshima survivors’ experience “death in life,” an encounter with the indescribable.

How does one represent what is beyond representation? In the film, Nolan recreates the intensity of the Trinity test with color and sound, following the bright flash with a pause and then the deep rumble and roar of the explosion and the clap of the shock wave. When it comes to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, however, he chooses to represent the attack without portraying it.

Drawing on a description in “American Prometheus,” the iconic biography of Oppenheimer on which the film was based, Nolan shows Oppenheimer’s triumphal speech in front of a cheering audience in the Los Alamos auditorium, announcing the destruction of Hiroshima by the weapon they had created.

Nolan creates a sense of dissociation, with the horror of the bomb entering the scene through flashbacks to the Trinity test and images of incinerated bodies from Hiroshima. The scientists’ cheering nightmarishly changes to wailing and weeping.

After the end of the war, many of the scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project sought to emphasize that the atomic bomb was not just another weapon. They argued that its tremendous danger should make war obsolete.

Among them, Oppenheimer carried the most authority as a result of his leadership of Los Alamos and his oratorical gifts. He pushed for arms control, playing the key role in drafting 1946’s Acheson-Lilienthal Report, a radical proposal that called for atomic energy to be placed under the control of the United Nations.

The form it ultimately took, known as the Baruch Plan, was rejected by the Soviet Union. Oppenheimer was bitterly disappointed, but U.S. atomic diplomats probably meant for it to be rejected – after all, the U.S. Navy was testing atomic bombs over the Bikini Atoll in the Pacific. Rather than seeing the bomb as the weapon to end all wars, the U.S. military seemed to treat it as its trump card. Nolan’s film includes a reference to the British physicist Patrick Blackett’s statement that the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was “not so much the last military act of the Second World War, as the first major operation of the cold diplomatic war with Russia.”

When the Soviets gained their own atomic bomb in 1949, Oppenheimer and his scientific advisory group opposed a proposal that the U.S. respond by pursuing the hydrogen bomb, a thousand times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. His opposition paved the way for Oppenheimer’s fall from political grace. Within a few years, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union had tested hydrogen bombs. The era of mutual assured destruction, when a nuclear attack would be certain to annihilate both superpowers, had begun. Today, nine nations have nuclear weapons – but 90% of them still belong to the U.S. and Russia.

Late in life, Oppenheimer was asked about the prospect of talks to limit the spread of nuclear weapons. “It’s 20 years too late,” he said. “It should have been done the day after Trinity.”

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. The Conversation has a variety of fascinating free newsletters.

Read more: Female physicists aren’t represented in the media – and this lack of representation hurts the physics field Data science education lacks a much-needed focus on ethics

Charles Thorpe does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.