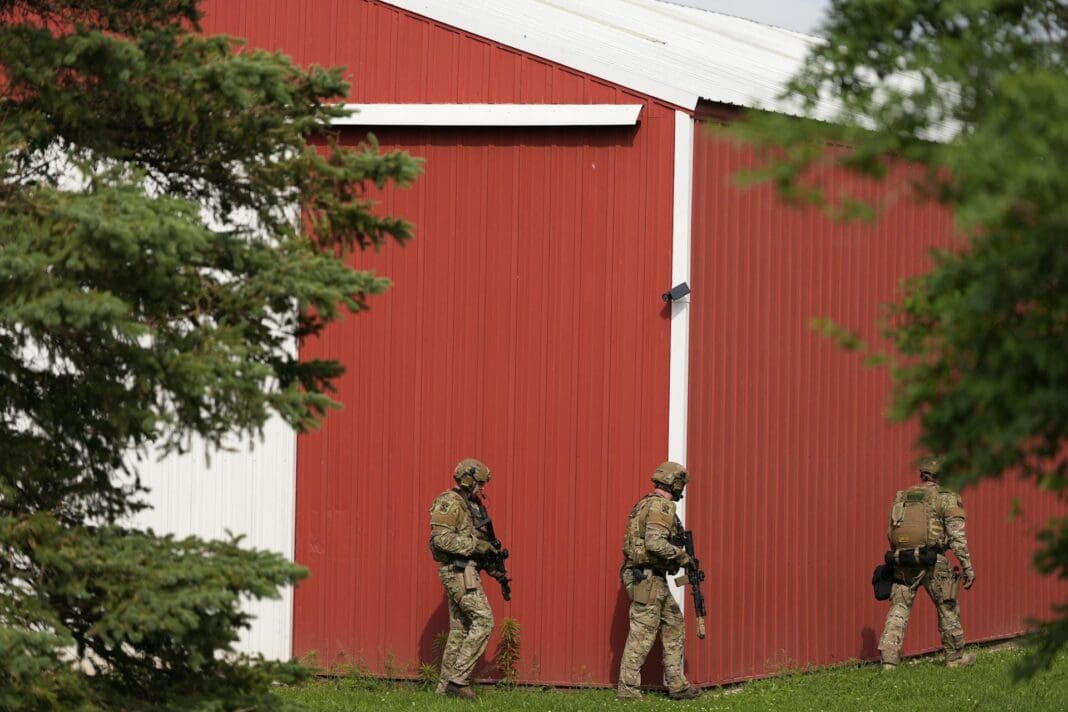

When shots rang out in Minnesota, targeting state Democratic politicians, the headlines quickly followed a familiar script: a mentally unstable suspect and the well-worn label “lone gunman.”

According to media reports, the Minnesota gunman, Vance Luther Boelter, was a deeply religious anti-abortion activist and a conservative who supported President Donald Trump.

The term lone gunman, routinely deployed in the aftermath of mass shootings and political violence – that the suspect was simply acting alone, so there’s no one or nothing else to blame – may offer a comforting explanation, but it’s dangerously simplistic.

It obscures the conditions that made the violence possible in the first place. It casts the perpetrator as an isolated anomaly – mentally unwell, unpredictable, detached from broader movements or ideologies.

As a scholar of extremism, I argue that the use of this term ignores the larger symptoms of deeper societal failures such as rising political extremism, systemic hate or the normalization of violent rhetoric.

The idea of the lone gunman has long held sway in American public discourse, with perhaps no example more iconic than the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The Warren Commission that was set up to investigate concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, a finding still contested by many.

But more significant than the historical debate is how the lone gunman label became entrenched in the national psyche. It presents a digestible narrative, one that absolves institutions of responsibility and short-circuits more difficult questions about what conditions produced the attacker in the first place.

More recent examples reveal how this myth continues to serve as a shield against systemic scrutiny.

After the 2012 mass shooting that killed 12 people and injured 70 others at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, media coverage quickly centered on James Holmes’ mental state, with little emphasis on the culture of gun access, misogyny or disaffection with peers that shaped his actions.

Similarly, after Dylann Roof murdered nine Black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015, early coverage emphasized his apparent isolation and mental state. However, he had openly stated his motivations in a racist manifesto and had long-standing connections to white supremacist ideology that motivated and shaped his violence.

In most cases, so-called lone wolves are not as isolated as the term implies. Researchers have increasingly shown that radicalization is a social process.

Individuals absorb extremist views through online echo chambers, algorithmic recommendation systems, peer validation and reinforcement from political and media figures.

This is evident in cases like that of Robert Bowers, who killed 11 people at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh in 2018. Bowers’ defense attorneys said in a March 2023 court filing that he had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Though he acted alone, Bowers was deeply embedded in far-right networks on the social media platform Gab, where he echoed white nationalist and antisemitic conspiracy theories.

Similarly, Payton Gendron, who killed 10 Black people in a Buffalo supermarket in 2022, cited previous mass shooters as inspiration and plagiarized sections of a white nationalist manifesto. His radicalization was nourished in extremist online forums on platforms such as 4chan and Discord.

Even attacks without manifestos or explicit ideological tracts often follow recognizable scripts. The El Paso shooter, who killed 23 people in a Walmart in 2019, wrote that he was targeting Hispanics as part of a defense against an “invasion” of immigrants – echoing language used by some conservative analysts, pundits and political figures in mainstream U.S. media and government.

Again and again, attackers are seen to be acting in ways that align with a broader rationalization or ideology, even if they do not carry official membership in a particular group or organization.

Importantly, the lone gunman narrative is applied unevenly, especially along racial lines.

White perpetrators are frequently described as mentally ill or troubled loners. Their violence is compartmentalized as the result of personal demons. In contrast, as the Sentencing Project – which is working to address racial disparities in the criminal justice system – has shown, Black, Muslim or immigrant suspects are often held up as proof of a broader threat: religious, ethnic or cultural.

This double standard not only reinforces racial stereotypes but also shapes how law enforcement and the media view violence committed by white actors – as an aberration rather than a pattern.

The media can play a crucial role in perpetuating the lone gunman myth. Consider how swiftly the media and politicians labeled the 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting, perpetrated by Omar Mateen, as an act of Islamist terrorism. Even though Mateen had no meaningful connections to any terrorist groups, his Islamic religious beliefs were used to construct a narrative that he was part of a global threat.

By contrast, the FBI hesitated to call Dylann Roof’s actions “racial terrorism.” Terrorism is defined as a form of political violence, where the threat or use of physical force by individuals or groups is not only intended to influence or disrupt governmental authority but to instill fear and force political change. The FBI designated Roof’s crime as a hate crime perpetrated by a disturbed young man.

This distinction between calling Roof’s attack a hate crime rather than racially motivated terrorism sparked significant criticism from scholars, activists and commentators. Many argued that Roof’s white supremacist motives and the symbolic target, a historic Black church, made it a clear case of racial terrorism.

This asymmetry matters.

I argue that it shapes public perception, policy responses and resource allocation. It allows white supremacist violence to flourish under the radar, often dismissed until it becomes undeniable – usually after multiple lives have been lost.

At the same time, politicians are frequently reluctant to acknowledge the ideological underpinnings of such violence, particularly when those ideologies overlap with their own rhetoric or voter base.

After the 2022 mass shooting in Buffalo, where the gunman explicitly cited the “Great Replacement theory” in his manifesto, several Republican politicians who had previously echoed similar anti-immigrant rhetoric condemned the violence but avoided addressing the ideology behind it. The Great Replacement theory is a white supremacist conspiracy theory that falsely claims white populations are being deliberately replaced by nonwhite immigrants, especially Muslims, Latinos or Black people, through immigration, higher birth rates and federal government policy.

Despite the shooter’s clear ideological motivation, once again many officials focused on mental illness or the violence as an isolated case of extremism. The impact of the messages about immigration and demographic change in contributing to a climate of racial fear and conspiracy were left unacknowledged.

The Department of Homeland Security has repeatedly identified white supremacist violence as one of the top domestic terrorism threats. Investigations related to domestic terrorism and violence have increased significantly over the past few years. In a 2023 interview with “PBS NewsHour,” Seamus Hughes of the University of Nebraska Omaha’s National Counterterrorism, Innovation, Technology and Education Center said that “the FBI was investigating 850 people three years ago. Now they’re investigating 2,700.”

Yet meaningful, structural reforms, whether in tech and social media regulation, gun control or public education, have remained elusive. I believe connecting the larger social, political and cultural issues that surround extreme violence is critical to building healthy communities.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Art Jipson, University of Dayton

Read more: Germany’s young Jewish and Muslim writers are speaking for themselves – exploring immigrant identity beyond stereotypes Protestantism’s troubling history with white supremacy in the US White supremacists who stormed US Capitol are only the most visible product of racism

Art Jipson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.