Literate in tone, far-reaching in scope, and witty to its bones, The New Yorker brought a new – and much-needed – sophistication to American journalism when it launched 100 years ago this month.

As I researched the history of U.S. journalism for my book “Covering America,” I became fascinated by the magazine’s origin story and the story of its founder, Harold Ross.

In a business full of characters, Ross fit right in. He never graduated from high school. With a gap-toothed smile and bristle-brush hair, he was frequently divorced and plagued by ulcers.

Ross devoted his adult life to one cause: The New Yorker magazine.

Born in 1892 in Aspen, Colorado, Ross worked out west as a reporter while still a teenager. When the U.S. entered World War I, Ross enlisted. He was sent to southern France, where he quickly deserted from his Army regiment and made his way to Paris, carrying his portable Corona typewriter. He joined up with the brand-new newspaper for soldiers, Stars and Stripes, which was so desperate for anybody with training that Ross was taken on with no questions asked, even though the paper was an official Army operation.

In Paris, Ross met a number of writers, including Jane Grant, who had been the first woman to work as a news reporter at The New York Times. She eventually became the first of Ross’ three wives.

After the armistice, Ross headed to New York City and never really left. There, he started meeting other writers, and he soon joined a clique of critics, dramatists and wits who gathered at the Round Table in the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street in Manhattan.

Over long and liquid lunches, Ross rubbed shoulders and wisecracked with some of the brightest lights in New York’s literary chandelier. The Round Table also spawned a floating poker game that involved Ross and his eventual financial backer, Raoul Fleischmann, of the famous yeast-making family.

In the mid-1920s, Ross decided to launch a weekly metropolitan magazine. He could see that the magazine business was booming, but he had no intention of copying anything that already existed. He wanted to publish a magazine that spoke directly to him and his friends – young city dwellers who’d spent time in Europe and were bored by the platitudes and predictable features found in most American periodicals.

First, though, Ross had to come up with a business plan.

The kind of smart-set readers Ross wanted were also desirable to Manhattan’s high-end retailers, so they got on board and expressed interest in buying ads. On that basis, Ross’ poker partner Fleischmann was willing to stake him US$25,000 to start – roughly $450,000 in today’s dollars.

In the fall of 1924, using an office owned by Fleischmann’s family at 25 West 45th St., Ross got to work on the prospectus for his magazine:

“The New Yorker will be a reflection in word and picture of metropolitan life. It will be human. Its general tenor will be one of gaiety, wit and satire, but it will be more than a jester. It will not be what is commonly called radical or highbrow. It will be what is commonly called sophisticated, in that it will assume a reasonable degree of enlightenment on the part of its readers. It will hate bunk.”

The magazine, he famously added, “is not edited for the old lady in Dubuque.”

In other words, The New Yorker was not going to respond to the news cycle, and it was not going to pander to middle America.

Ross’ only criterion would be whether a story was interesting – with Ross the arbiter of what counted as interesting. He was putting all his chips on the long-shot idea that there were enough people who shared his interests – or could discover that they did – to support a glossy, cheeky, witty weekly.

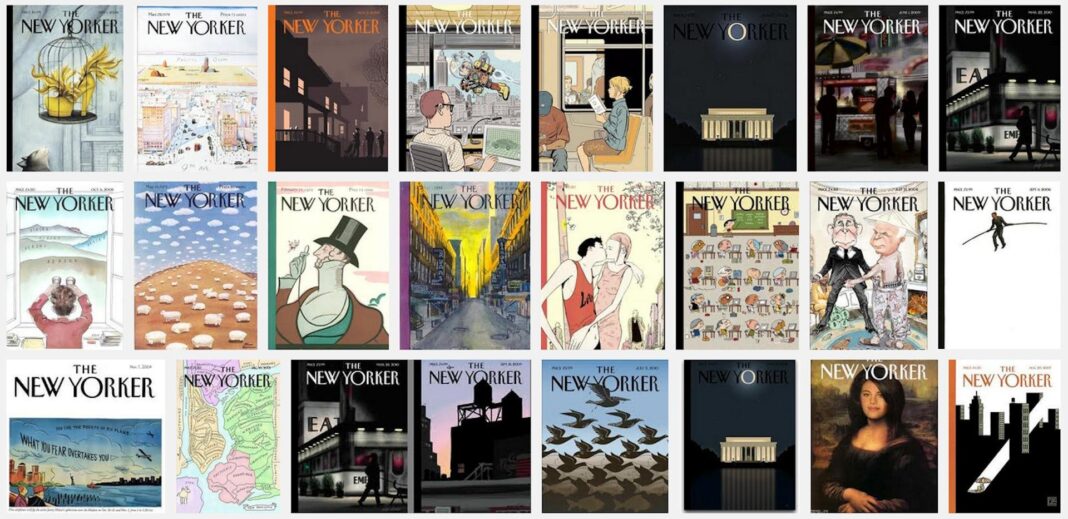

Ross almost failed. The cover of the first issue of The New Yorker, dated Feb. 21, 1925, carried no portraits of potentates or tycoons, no headlines, no come-ons.

Instead, it featured a watercolor by Ross’ artist friend Rea Irvin of a dandified figure staring intently through a monocle at – of all things! – a butterfly. That image, nicknamed Eustace Tilly, became the magazine’s unoffical emblem.

Inside that first edition, a reader would find a buffet of jokes and short poems. There was a profile, reviews of plays and books, lots of gossip, and a few ads.

It was not terribly impressive, feeling quite patched together, and at first the magazine struggled. When The New Yorker was just a few months old, Ross almost even lost it entirely one night in a drunken poker game at the home of Pulitzer Prize winner and Round Table regular Herbert Bayard Swope. Ross didn’t make it home until noon the next day, and when he woke, his wife found IOUs in his pockets amounting to nearly $30,000.

Fleischmann, who had been at the card game but left at a decent hour, was furious. Somehow, Ross persuaded Fleischmann to pay off some of his debt and let Ross work off the rest. Just in time, The New Yorker began gaining readers, and more advertisers soon followed. Ross eventually settled up with his financial angel.

A big part of the magazine’s success was Ross’ genius for spotting talent and encouraging them to develop their own voices. One of the founding editor’s key early finds was Katharine S. Angell, who became the magazine’s first fiction editor and a reliable reservoir of good sense. In 1926, Ross brought James Thurber and E.B. White aboard, and they performed a variety of chores: writing “casuals,” which were short satirical essays, cartooning, creating captions for others’ drawings, reporting Talk of the Town pieces and offering commentary.

As The New Yorker found its footing, the writers and editors began perfecting some of its trademark features: the deep profile, ideally written about someone who was not strictly in the news but who deserved to be better known; long, deeply reported, nonfiction narratives; short stories and poetry; and, of course, the single-panel cartoons and the humor sketches.

Intensely curious and obsessively correct in matters grammatical, Ross would go to any length to ensure accuracy. Writers got their drafts back from Ross covered in penciled queries demanding dates, sources and endless fact-checking. One trademark Ross query was “Who he?”

During the 1930s, while the country was suffering through a relentless economic depression, The New Yorker was sometimes faulted for blithely ignoring the seriousness of the nation’s problems. In the pages of The New Yorker, life was almost always amusing, attractive and fun.

The New Yorker really came into its own, both financially and editorially, during World War II. It finally found its voice, one that was curious, international, searching and, ultimately, quite serious.

Ross also discovered still more writers, such as A.J. Liebling, Mollie Panter-Downes and John Hersey, who was raided from Henry Luce’s Time magazine. Together, they produced some of the best writing of the war, most notably Hersey’s landmark reporting on the use of the first atomic bomb in warfare.

Over the past century, The New Yorker had a profound impact on American journalism.

For one thing, Ross created conditions for distinctive voices to be heard. For another, The New Yorker provided encouragement and an outlet for nonacademic authority to flourish; it was a place where all those serious amateurs could write about the Dead Sea Scrolls or geology or medicine or nuclear war with no credentials other than their own ability to observe closely, think clearly and put together a good sentence.

Finally, Ross must be credited with expanding the scope of journalism far beyond standard categories of crime and courts, politics and sports. In the pages of The New Yorker, readers almost never found the same content that they’d come across in other newspapers and magazines.

Instead, readers of The New Yorker might find just about anything else.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Christopher B. Daly, Boston University

Read more: The magazine that inspired Rolling Stone Before Breitbart, there was the Charleston News and Courier A century ago, progressives were the ones shouting ‘fake news’

Christopher B. Daly does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.