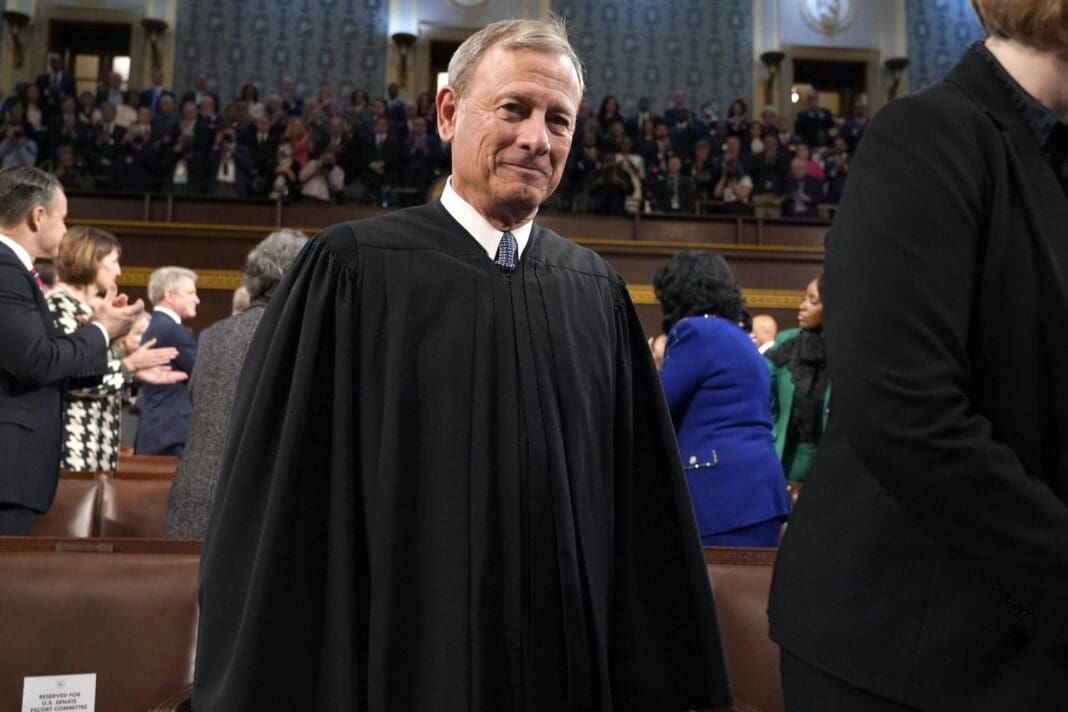

In two cases before the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2023 summer recess, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote majority opinions that involved the use of race.

In the court’s 5-4 Allen v. Milligan decision, Roberts wrote that states must consider race in some circumstances when drawing congressional districts.

But in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard College – and its companion case involving the University of North Carolina – Roberts virtually eliminated the use of race in college admissions.

Though Roberts’ opinions appear at odds, his general disdain for the use of race is not. In both cases, he was clear that his preference is for as little use of race as possible, a position he has held for decades.

As he famously wrote in a 2007 case that limited the use of race in school integration plans, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating based on race.”

At issue in the Alabama case was whether the power of Black voters was diluted by dividing them into districts where white voters dominate.

After the 2020 census, the Republican-controlled Alabama legislature redrew the state’s seven congressional districts to include only one in which Black voters would likely be able to elect a candidate of their choosing.

Black residents make up about 27% of the state’s population, and voting rights advocates argued that they deserved not one but two political districts.

In its ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court relied on a nearly 40-year-old case, Thornburg v. Gingles, that determined a state should often draw a majority-minority district if three conditions are met.

First, if the racial minority can be a majority in a reasonably drawn district. Second, if the racial minority is politically cohesive, meaning that its members tend to vote together for the same candidates. And third, if the racial minority faces bloc voting by a racial majority that tends to vote against the racial minority’s candidate of choice.

All three conditions were true in Alabama, and the totality of the circumstances suggested minority voters did not participate equally in the political process in the area.

In his opinion, Roberts explained how racially motivated voter suppression in the century after the Civil War led to the initial passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“A district is not equally open,” Roberts wrote, “when minority voters face – unlike their majority peers – bloc voting along racial lines, arising against the backdrop of substantial racial discrimination within the State, that renders a minority vote unequal to a vote by a nonminority voter.”

Given the court’s recent history of restricting rights protected under the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 – and Roberts’ past opposition – Roberts’ opinion surprised many civil and voting rights advocates.

“States shouldn’t let race be the primary factor in deciding how to draw boundaries, but it should be a consideration,” Roberts wrote. “The line we have drawn is between consciousness and predominance.”

That line of thinking is a far cry from Roberts’ unrelenting opposition to key provisions of the Voting Rights Act. In the 1980s, as a young lawyer in the U.S. Justice Department during the Reagan administration, Roberts wrote 25 memos in opposition to the Voting Rights Act.

Roberts went even further as chief justice. In the 2013 Shelby County v. Holder case, Roberts and the court’s conservative majority eliminated provisions of the Voting Rights Act that required states with a history of voting discrimination to get voting changes cleared by the federal government before they went into effect.

Roberts had a different view of race and its importance in diversifying college campuses.

The anti-affirmative action organization Students for Fair Admissions argued that the schools’ race-conscious admissions process was unconstitutional and discriminated against high-achieving Asian American students in favor of traditionally underrepresented Blacks and Hispanics who may not have earned the same grades or standardized test scores as other applicants, such as Asian Americans.

Roberts agreed in his majority opinion.

He argued that the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment – and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act – strictly limited how schools could use race in admissions.

“College admissions are zero sum, and a benefit provided to some applicants but not to others necessarily advantages the former at the expense of the latter,” Roberts wrote.

Though Roberts could have used previous U.S. Supreme Court decisions in 1978’s Regents of the University of California v. Bakke or its 2003 Grutter v. Bollinger decision to continue to allow the use of race in college admissions, he did not.

Those cases, he argued, had been interpreted too permissively by schools. He wrote that Harvard’s and UNC’s race-infused admissions guidelines “cannot be reconciled with the guarantees of the Equal Protection Clause.”

But near the end of his opinion, Roberts appears to backtrack slightly by writing that each prospective student should be evaluated “as an individual – not on the basis of race,” although universities can still consider “an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.”

Roberts’ arguments for the conflicting rulings on the use of race may appear puzzling.

In the Alabama case, Roberts ruled that the law requires the state to explicitly use race to ensure minority race voters who are currently being shut out of the political process may receive their fair share of representation.

In the affirmative action cases, Roberts ruled that the law prevents universities from explicitly using race to ensure minority race applicants who have historically been shut out of the admissions process may be admitted in even rough proportion to their population.

In both circumstances, the use of race worked as a corrective to discriminatory voting laws and college admissions practices.

In congressional redistricting, race is used to build districts to counter racial bloc voting and de facto residential and ideological segregation. In admissions, race was used to increase diversity that helped the learning atmosphere for all students. It also had the effect of adding underrepresented minority students with diverse backgrounds to student bodies.

In her dissent in the North Carolina affirmative action case, Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson spells out the problem with Roberts’ ambivalence on race.

“With let-them-eat-cake obliviousness,” Jackson wrote, “the majority pulls the rip cord and announces ‘colorblindness for all’ by legal fiat. But deeming race irrelevant in law does not make it so in life.”

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. Like this article? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Read more: Affirmative action lasted over 50 years: 3 essential reads explaining how it ended Support for legacy admissions is rooted in racial hierarchy

Henry L. Chambers Jr. does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.