For most American Jews today, Shavuot is not exactly a big-ticket holiday. Observance lags behind springtime Passover, and it pales in comparison to Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, the fall “high holidays.”

But 150 years ago, Shavuot was the one day when everybody wanted to be in synagogue: It was a day to celebrate children.

As a scholar of American religion and Judaism, I have written about how the history of religious education reveals the changing ways that American Jews have imagined Judaism itself. The history of Shavuot, which begins at sundown on May 25 in 2023, offers a fascinating illustration of these dynamics.

In ancient times, Shavuot was an agricultural pilgrimage festival, a time to bring offerings of first grains and fruits to the temple in Jerusalem.

After the Romans destroyed the temple in 70 C.E., Jewish leaders redesignated Shavuot as a holiday that would primarily commemorate the revelation of the Torah. According to Jewish tradition, God gave these teachings to Moses on Mt. Sinai as he led the Israelites through the desert.

Jews have traditionally described the Torah as the word of God – a text potent with significance. Shavuot became a time to celebrate the study of the Torah and its many rabbinic commentaries, including the Mishnah and the Talmud.

Shavuot has long been marked by customs that include “Tikkun Leil Shavuot,” gathering with others to study Torah late into the night. And it has been celebrated with dairy-based foods like blintzes and cheesecakes – treats that signify, among other ideas, that the Torah is the “milk” that nourishes the Jewish people.

Jews began to establish communities in North America beginning in the 17th century. On Shavuot, they continued the long-standing custom of celebrating the revelation of the Torah with synagogue services and late-night study.

By the mid-late 19th century, however, many American Jews had begun to neglect these traditional observances. Some felt increasingly uneasy with a holiday that rested on the premise of biblical revelation. At the time, an academic field called biblical criticism was growing and gaining influence. These academics analyzed the Bible’s development as a historical text, identifying it as an anthology of human writers. This left many religious people wrestling with the traditional idea of scripture as the divine word of God.

What, then, to do with Shavuot? A new ceremony introduced by Jews in Europe in the early 1800s offered a promising alternative: confirmation.

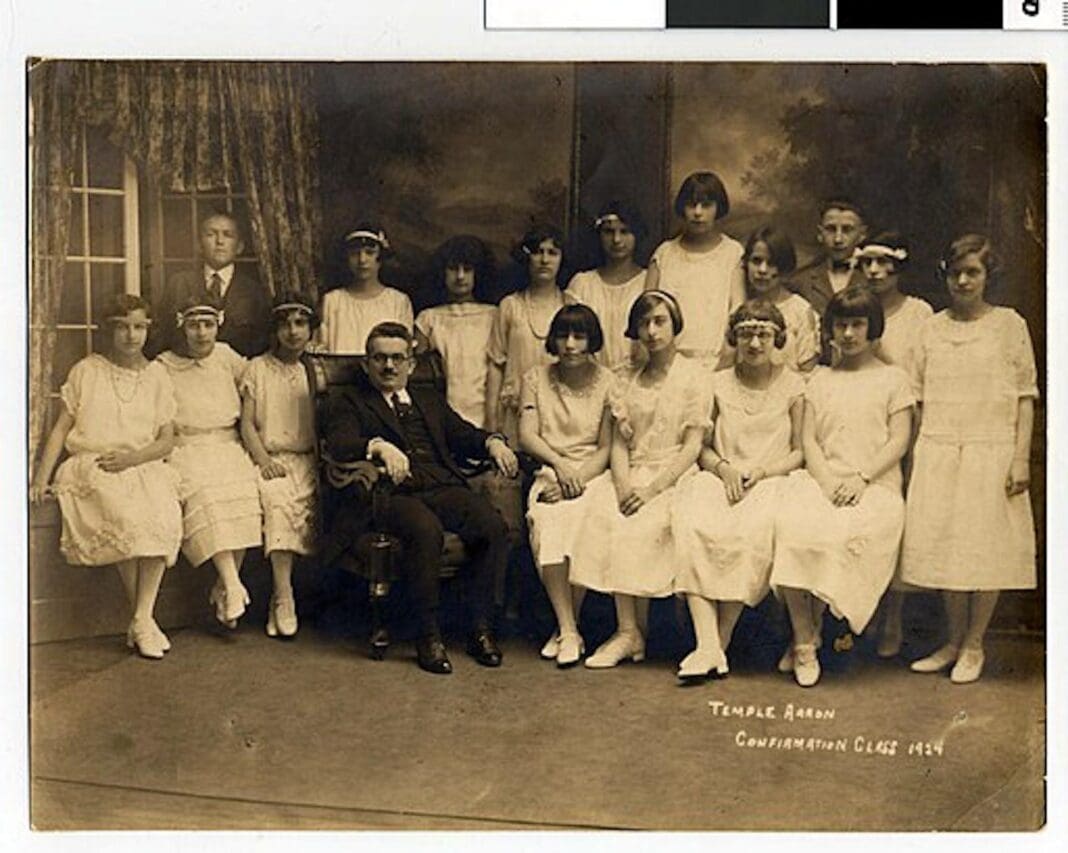

Beginning in the mid-19th century, American Jews began to reimagine Shavuot as the time for grandiose celebrations of children’s graduation from Jewish Sunday Schools. On the morning of Shavuot or the closest weekend to it, the students being confirmed, usually 12 or 13 years old, would dress up in fine clothes and parade to the front of their synagogue sanctuaries.

Each child would typically carry elaborate bouquets of flowers, which were essential to the pageantry. Different blooms symbolized religious virtues of the children. White lilies, for example, symbolized innocence and purity, and were often incorporated into the children’s bouquets, as well as into elaborate floral decorations that bedecked the synagogue interior.

Participants would recite declarations of their belief in the one God of the Jewish people and give speeches that confirmed their commitments to Judaism. They would be tested on their “catechisms,” short books that recorded questions and answers about religion that children were expected to memorize. To mark the children’s coming of age, rabbis would confer a blessing, welcoming them as adult members of the congregation.

The ceremony would conclude with parties and celebrations and elaborate gifts, particularly for the offspring of wealthier families.

For many American Jews, confirmation was appealing as a gender-inclusive coming-of-age ritual. In some congregations, it replaced the bar mitzvah, a ceremony that was traditionally restricted to boys when they reached age 13. In other synagogues, confirmation was introduced as a supplemental ceremony held at the end of the school year.

Confirmation was not, however, a traditionally Jewish practice. It was a Christian ceremony for coming of age that Jews adopted in the 19th century – first in Europe and then across the Atlantic.

In the U.S., confirmation ceremonies appealed to Jews because they offered a prime moment to show outsiders that Judaism could “fit in” to an American culture dominated by Protestant Christianity. The American Jewish Reform movement, which in the 19th century became the largest American Jewish denomination, believed that Judaism should be adapted so that it was more relevant to contemporary life.

Reform Jews celebrated confirmation with spectacular floral displays, musical accompaniments and extravagant decorations. These grand spectacles were designed to draw huge crowds to the synagogue – not only Jews, but non-Jewish visitors as well. Jews were sensitive to how Christian outsiders perceived their religion, and Shavuot became a day to show that Jewish ceremonies could rival the grandest holiday celebrations put on by Christian churches.

Not only that, but confirmation also quelled American Jewish anxieties about the future. By putting children promising their commitments to the Jewish people at the center of the stage, confirmation ceremonies reassured American Jews that the next generation was committed to Jewish life.

As the 20th century dawned, the concerns of American Jewish educators began to shift. Over 2.5 million Jewish immigrants arrived in the U.S. between 1881 and 1924, including many who were committed to traditional Jewish practice. The demographics of American Judaism were changing, and American Jewish education began to change, too.

In the Reform movement, educators re-embraced aspects of Jewish tradition that they had previously rejected. They put down their English-language catechisms and returned to teaching Hebrew. They returned to the bar mitzvah too, expanding the ceremony so that girls too could have their own special Jewish day.

Confirmation didn’t go away, but it was reorganized as a ceremony for older children. By deferring confirmation so that it aligned more with graduation from high school, Jewish educators sought to incentivize children to remain in Jewish education throughout their teenage years.

Today, many American synagogues still celebrate confirmations around Shavuot, though they are no longer billed as the highlight of the Jewish year. The echoes of the 19th century still linger, however, in every American synagogue where Shavuot is a time for young people to don white robes and confirm their commitments to Judaism – and not only a holiday to study Torah and enjoy a cheesecake buffet.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. Like this article? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Read more: Ancient DNA from the teeth of 14th-century Ashkenazi Jews in Germany already included genetic variations common in modern Jews ‘Untraditional’ Hanukkah celebrations are often full of traditions for Jews of color

Laura Yares has received funding for her research from The American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, Ohio