On the night of July 1, 1839, 53 enslaved Africans revolted aboard the slaving schooner La Amistad – Spanish for “Friendship” – while they were being shipped to a plantation in Puerto Príncipe, Cuba.

Kidnapped and trafficked from modern-day Sierra Leone to Havana on a larger vessel, they had been transferred to the smaller La Amistad to reach Puerto Príncipe.

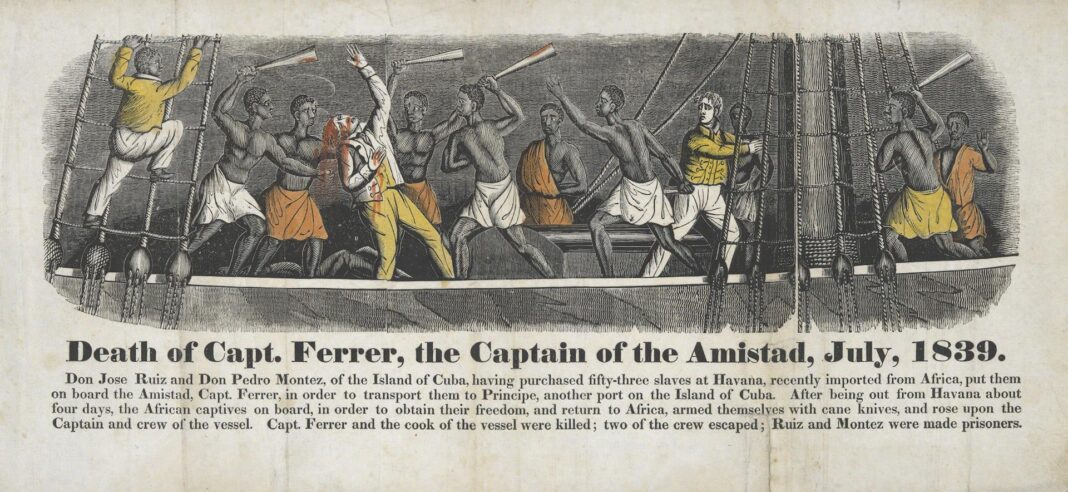

A 25-year-old man named Sengbe Pieh led the rebels, who suffered 10 fatalities in the fray. They still managed to kill the captain, Ramon Ferrer, and take control of the ship, ordering the surviving crew to return them to Sierra Leone. But the crew instead sailed the vessel north, where it was captured in Long Island Sound.

With the rebels detained in Connecticut, their fate would be decided by the state’s legal system.

A remarkable set of 22 drawings reveal the faces of these rebels, providing a rare glimpse into their humanity when they were affirming their right to live free.

I served as the lead historian and researcher for an exhibition where three of these portraits are now on display, “In Slavery’s Wake: Making Black Freedom in the World,” at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

In 1808, the United States, along with a host of other countries, banned the participation of its citizens in the transportation of enslaved people from Africa to the Americas. Nonetheless, at least 2.8 million Africans were brought to the Americas between 1808 and 1866, primarily to work on sugar plantations in Brazil and Cuba. Shippers, plantation owners, merchants and crews reaped massive profits.

But historians know very little about the individuals aboard these slave ships. More often than not, their existence was reflected in numbers on ledgers and spreadsheets. Their birth names, birth dates, family histories – anything that would have humanized them – were hard to come by.

Portraits of enslaved people from the 19th century were also unusual. Enslavers often viewed them as mere chattel and not worth the expense and effort of commissioning a painting. If they did appear in art, it was in the background as loyal servants, helpless victims or stereotypical brutes.

That’s what makes these drawings, created by Connecticut artist William H. Townsend during the trial, so remarkable.

Historians don’t know exactly why Townsend decided to draw them, only that he lived locally and sat in the courtroom during the trial. In 1934, these portraits were donated to Yale University’s Beinecke Library by one of Townsend’s descendants.

While his motivations for drawing these portraits remain unclear, the humanity he depicted is clear. The expressions of his subjects often evoke both their resistance and their desire for freedom.

Fuli, one of several captives who had stolen water on board the vessel and had been ordered flogged by Captain Ferrer during the voyage, gazes at the viewer with a solemn, self-possessed air. It’s easy to imagine him as a leader steeled by all the suffering he experienced over the course of his journey.

Marqu – or Margru – was one of the three young girls who were aboard the Amistad. In her portrait, she gently smiles – a glint of a personality that’s persevered despite the trauma of the voyage and her time spent in prison awaiting trial.

Grabo – or Grabeau – was second-in-command to Pieh in the revolt. He was a rice planter and was married at the time of his capture, and was enslaved to repay a debt his family owed. In his portrait, he gazes with his eyebrows raised – inquisitive, proud and at ease.

Despite their different facial expressions, the three appear to be united in their collective determination to be agents in their own liberation. In Pieh’s words: “Brothers, we have done that which we purposed. … I am resolved it is better to die than to be a white man’s slave.”

The lawyers hired by abolitionists to represent the 53 surviving rebels – Roger S. Baldwin, Theodore Sedgwick and Seth Staples – argued that they rebelled because “each of them are natives of Africa and were born free, and ever since have been and still of right are and ought to be free and not slaves.”

Eventually, the case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court. The court found that because the captives aboard the Amistad were free at the time of their capture in Long Island, they could not be considered property of Spain.

The verdict became a landmark case for litigating the illegal slave trade, which continued to expand over the next two decades until finally ending in the 1860s. The Amistad rebels inspired other captives: In 1841, as the American ship Creole traveled between Richmond, Virginia, and New Orleans, those on board revolted, wresting control of the ship and sailing it to the Bahamas, where they eventually gained their freedom.

These portraits, like the testimony in court and the revolt onboard the Amistad, bring the massive, messy, contested story of slavery down to the scale of individual humans. Their visages call upon present and future generations to collectively imagine not only the horrors of the slave trade, but also the power of individual dignity and collective resistance.

They light the darkness – in the 1840s and in the world today.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Kate McMahon, Smithsonian Institution

Read more: The Napoléon that Ridley Scott and Hollywood won’t let you see A digital archive of slave voyages details the largest forced migration in history In ‘The Good Lord Bird,’ a new version of John Brown rides in at a crucial moment in US history

Kate McMahon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.