Humans will likely set foot on the Moon again in the coming decade. While many stories in this new chapter of lunar exploration will be reminiscent of the Apollo missions 50 years ago, others may look quite different.

For instance, the European Space Agency is currently working to make space travel more accessible for people of a wide range of backgrounds and abilities. In this new era, the first footprint on the Moon could possibly be made by a prosthetic limb.

Historically, and even still today, astronauts selected to fly to space have had to fit a long list of physical requirements. However, many professionals in the field are beginning to acknowledge that these requirements stem from outdated assumptions.

Some research, including studies by our multidisciplinary team of aerospace and biomechanics researchers, has begun to explore the possibilities for people with physical disabilities to venture into space, visit the Moon and eventually travel to Mars.

NASA has previously funded and is currently funding research on restraints and mobility aids to help everyone, regardless of their ability, move around in the crew cabin.

Additionally, NASA has research programs to develop functional aids for individuals with disabilities in current U.S. spacecraft. A functional aid is any device that improves someone’s independence, mobility or daily living tasks by compensating for their physical limitations.

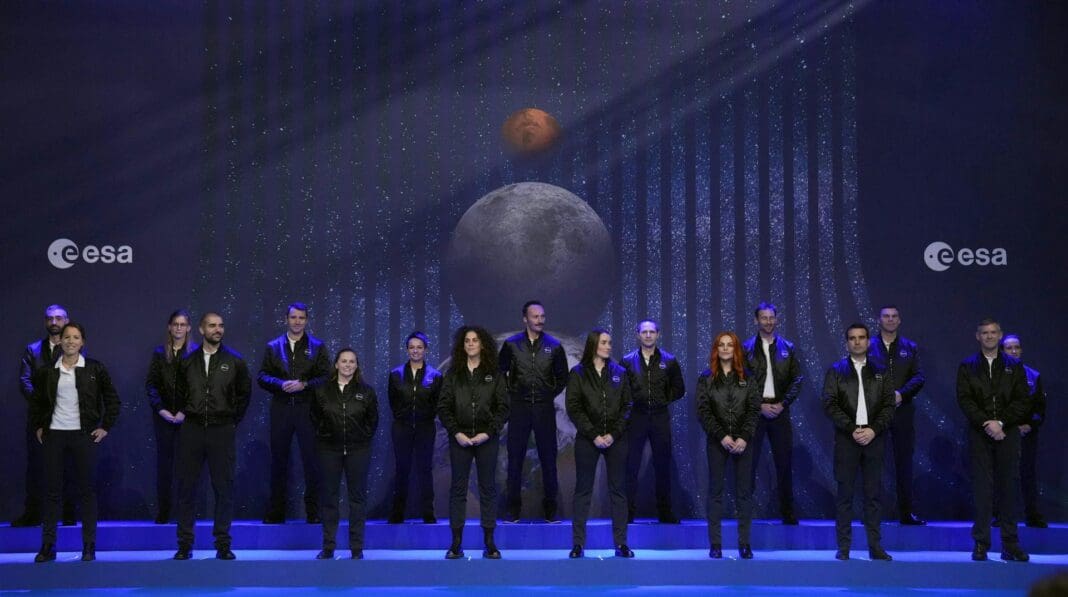

The European Space Agency, or ESA, launched its Parastronaut Feasibility Project in 2022 to assess ways to include individuals with disabilities in human spaceflight. A parastronaut is an astronaut with a physical disability who has been selected and trained to participate in space missions.

At the University of North Dakota, we conducted one of the first studies focused on parastronauts. This research examined how individuals with disabilities get into and get out of two current U.S. spacecraft designed to carry crew. The first was NASA’s Orion capsule, designed by Lockheed Martin, and the second was Boeing’s CST 100 Starliner.

Alongside our colleagues Pablo De León, Keith Crisman, Komal Mangle and Kavya Manyapu, we uncovered valuable insights into the accessibility challenges future parastronauts may face.

Our research indicated that individuals with physical disabilities are nearly as nimble in modern U.S. spacecraft as nondisabled individuals. This work focused on testing individuals who have experienced leg amputations. Now we are looking ahead to solutions that could benefit astronauts of all abilities.

John McFall is the ESA’s first parastronaut. At the age of 19, Mcfall lost his right leg just above the knee from a motorcycle accident. Although McFall has not been assigned to a mission yet, he is the first person with a physical disability to be medically certified for an ISS mission.

Astronaut selection criteria currently prioritize peak physical fitness, with the goal of having multiple crew members who can do the same physical tasks. Integrating parastronauts into the crew has required balancing mission security and accessibility.

However, with advancements in technology, spacecraft design and assistive tools, inclusion no longer needs to come at the expense of safety. These technologies are still in their infancy, but research and efforts like the ESA’s program will help improve them.

Design and development of spacecraft can cost billions of dollars. Simple adaptations, such as adding handholds onto the walls in a spacecraft, can provide vital assistance. However, adding handles to existing spacecraft will be costly.

Functional aids that don’t alter the spacecraft itself – such as accessories carried by each astronaut – could be another way forward. For example, adding Velcro to certain spots in the spacecraft or on prosthetic limbs could improve a parastronaut’s traction and help them anchor to the spacecraft’s surfaces.

Engineers could design new prosthetics made for particular space environments, such as zero or partial gravity, or even tailored to specific spacecraft. This approach is kind of like designing specialized prosthetics for rock climbing, running or other sports.

Future space exploration, particularly missions to the Moon and Mars that will take weeks, months and even years, may prompt new standards for astronaut fitness. During these long missions, astronauts could get injured, causing what can be considered incidental disability.

An astronaut with an incidental disability begins a mission without a recognized disability but acquires one from a mission mishap. An astronaut suffering a broken arm or a traumatic brain injury during a mission would have a persistent impairment.

During long-duration missions, an astronaut crew will be too far away to receive outside medical help – they’ll have to deal with these issues on their own.

Considering disability during mission planning goes beyond inclusion. It makes the mission safer for all astronauts by preparing them for anything that could go wrong. Any astronaut could suffer an incidental disability during their journey.

Safety and inclusion in spaceflight don’t need to be at odds. Instead, agencies can reengineer systems and training processes to ensure that more people can safely participate in space missions. By addressing safety concerns through technology, innovative design and mission planning, the space industry can have inclusive and successful missions.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Jesse Rhoades, University of North Dakota and Rebecca Rhoades, University of North Dakota

Read more: Why including people with disabilities in the workforce and higher education benefits everyone A giant leap for humankind – future Moon missions will include diverse astronauts and more partners SpaceX Inspiration4 mission sent 4 people with minimal training into orbit – and brought space tourism closer to reality

Jesse Rhoades receives funding from NASA.

Rebecca Rhoades does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.