I was 9 years old when Eric B. and Rakim’s “Paid in Full” dropped. I have vivid memories of the bass-laden track booming out of car stereos and hearing it on Black radio, like Kiss FM’s top eight at 8 p.m. countdown.

On the track “Move the Crowd,” Rakim – also known as “the God MC” – rhymes “All praise is due to Allah and that’s a blessing.” Growing up as a Black Muslim in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, I was already familiar with the phrase. Like all Muslims, I learned to say it during my daily prayers and as an expression of gratitude.

But when Rakim laced those words into the lyrics of what ultimately became a popular song, he affirmed what I was seeing around me in my Brooklyn community – that Islam and Muslims were prominent features of Black life.

Rakim dropped another familiar phrase in the song: knowledge of self.

When Rakim extols the benefits of “knowledge of self” to himself as an emcee and a human being, he is drawing on a philosophy that has been critical to Black Islam, a term I use to describe the different forms of Islamic belief and practice found in Black America.

Knowledge of self comes from this tradition, beginning roughly a century ago, which has become known for advancing Black consciousness, resistance and redemption. Knowledge of self is an ethical pursuit to understand one’s place in and relationship to the world in order to positively change it.

In my 2016 book, “Muslim Cool: Race, Religion and Hip Hop in the United States,” I demonstrate how knowledge of self is fundamental to hip-hop. It is often described as hip-hop’s “fifth element,” the others being DJing; emceeing or “rhyming”; graffiti or “writing”; and dance, from “b-boying” to “pop locking.”

While the phrase and the consciousness that it represents have been mentioned in too many songs to count – from Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” to Lauryn Hill’s “Doo Wop” and Talib Kweli’s “K.O.S. (Determination)” – history shows the term has been a part of Islamic literature for nearly a millennium. For example, the first chapter of the celebrated 12th-century Islamic scholar Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali’s famous text “The Alchemy of Happiness” is titled “The Knowledge of Self.”

In my book, I make the case that Islam, specifically Black Islam, gave hip-hip knowledge of self.

Rakim’s reference to knowledge of self’s being an “actual fact” is a nod to the “actual facts” of the “Lost-Found Muslim Lessons,” the catechism taught by Master W.D. Fard Muhammad, who founded the Nation of Islam on July 4, 1930. Master Fard taught these lessons to the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, who would become the religious movement’s leader.

These lessons are fundamental to the way that the Nation of Islam understands the world and the role of Black people in it. The lessons are also studied by the Nation of Gods and Earths, a related spiritual path, of which Rakim is a member. Knowledge of self comes to hip-hop through these lessons.

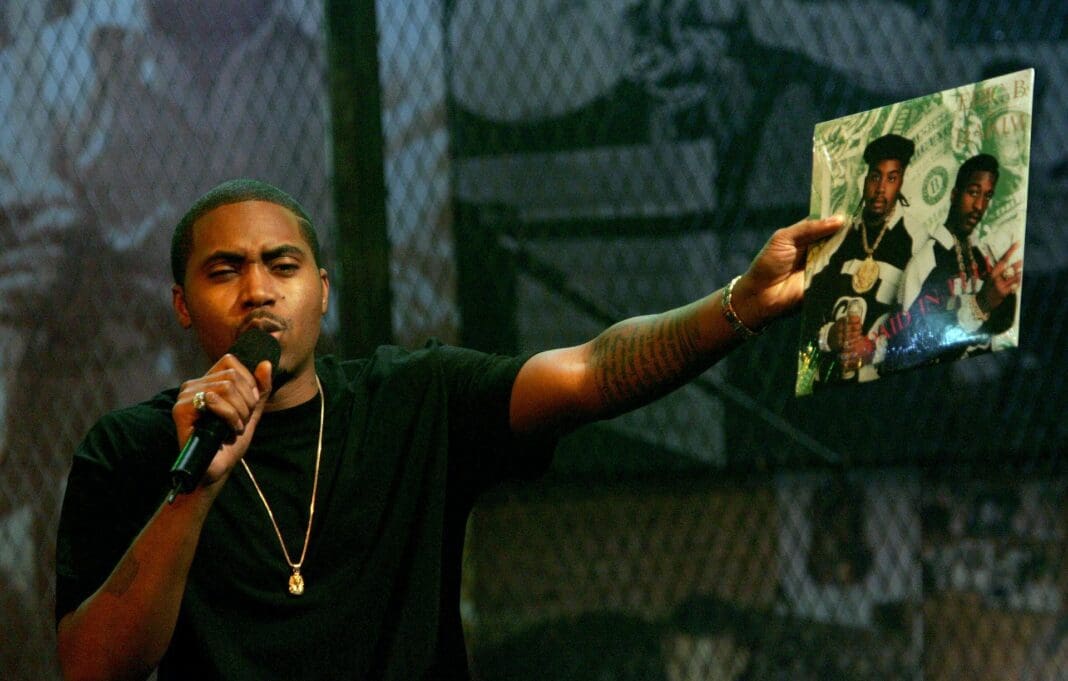

Rakim was not alone. During the golden age of hip-hop, a period from about the mid-1980s through mid-1990s, rappers – influenced by Black Islam – steadily proclaimed their knowledge of self in their music. Big Daddy Kane declared there’s “no pork on my fork,” an acknowledgment of the Islamic injunction against the consumption of swine. The Poor Righteous Teachers gave the Arabic greeting as salaamu alaikum with the dome of Harlem’s Masjid Malcolm Shabazz in the background in the music video for “Rock Dis Funky Joint.” And from Brooklyn to the California Bay, acclaimed emcees like Guru and local acts were rhyming about “praying to the east,” a reference to the Muslim practice.

Long before rappers spoke of knowledge of self in the 1980s, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad expounded on the term in his book “Message to the Blackman in America,” released in 1965 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. In it, he emphasized Black self-reliance – with knowledge of self being a key component.

“The so-called Negroes must be taught and given Islam,” Muhammad wrote. “Why Islam? Islam, because it teaches first the knowledge of self. It gives us the knowledge of our own. Then and only then are we able to understand that which surrounds us … this kind of thinking produces an industrious people who are self-independent.”

In some ways, it comes as little surprise that a term promulgated by a fierce advocate of self-reliance in the mid-1960s would be so widely embraced by hip-hop shortly after it was born as a counterculture in the early 1970s.

When Black Islam helped hip-hop culture cultivate knowledge of self, it created an aspiration, arguably unique for contemporary popular music as a whole, to not just rhyme about it or write graffiti about it, and so on, but to apply it in real life. As a result, knowledge of self became hip-hop’s consciousness, emphasizing an awareness of injustice and the imperative to address it through both personal and social transformation. Critically, this consciousness, while informed by Black Islam, is embraced by hip-hop community members of all stripes.

The consciousness led to different forms of hip-hop-based activism. Songs against gun violence like The Stop the Violence Movement’s “Self-Destruction” and “We Are All in the Same Gang” by the West Coast All Stars.

“Self-Destruction” opens, not inconsequentially, with a sample of a speech by Malcolm X, the onetime spokesman for the Nation of Islam and icon of Black Islam. The consciousness also contributed to the formation in 2004 of the National Hip-Hop Political Convention, which set the stage for other, albeit less radical and comprehensive, engagements with politics by the hip-hop generation, like the Vote or Die campaign and the push for Obama in 2008.

Nearly 10 years later, this consciousness was on display at the 2017 Grammy performance by A Tribe Called Quest, Busta Rhymes and Consequence that was an open call to “resist” in the Trump era. This consciousness also continues to inspire the many organizations like Kuumba Lynx and the Inner-City Muslim Action Network in Chicago that use hip-hop as a form of arts-based activism for youth.

And, of course, it remains in the music.

On the track “Family Feud,” Jay-Z – like Rakim – praises God, but this time in Arabic: “Alhamdulillah,” Mumu Fresh questions others’ knowledge of self with the line “Good morning, sunshine, welcome to reality/I tried to wake you, but you were sleepin’ so peacefully in your fallacy.” Busta Rhymes dropped “Extinction Level Event 2: The Wrath of God,” full of warnings and prophecies. And in a freestyle viewed around the world, Black Thought rhymes about the wisdom he got at the masjid. This consciousness is so entwined with music that Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” became a Black Lives Matter movement anthem.

Like hip-hop, this consciousness operates globally. Take, for example, the Iraqi-Canadian Narcy, Cape Town’s YoungstaCPT, Cuban hip-hop artist Robe L. Ninho and the U.K.’s Enny, whose works track their own journey for knowledge of self.

Things have changed since Rakim dropped “Move the Crowd” in 1987. Gentrification is pushing my community out of Brooklyn, and Islam and Muslims are more known and subject to the state and interpersonal violence of anti-Muslim racism. Yet hip-hop still affirms what I see around me – knowledge of self is as vital as ever.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. The Conversation is trustworthy news from experts, from an independent nonprofit. Try our free newsletters.

Read more: Hip-hop and health – why so many rap artists die young After ‘Rapper’s Delight,’ hip-hop went global – its impact has been massive; so too efforts to keep it real

Su'ad Abdul Khabeer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.