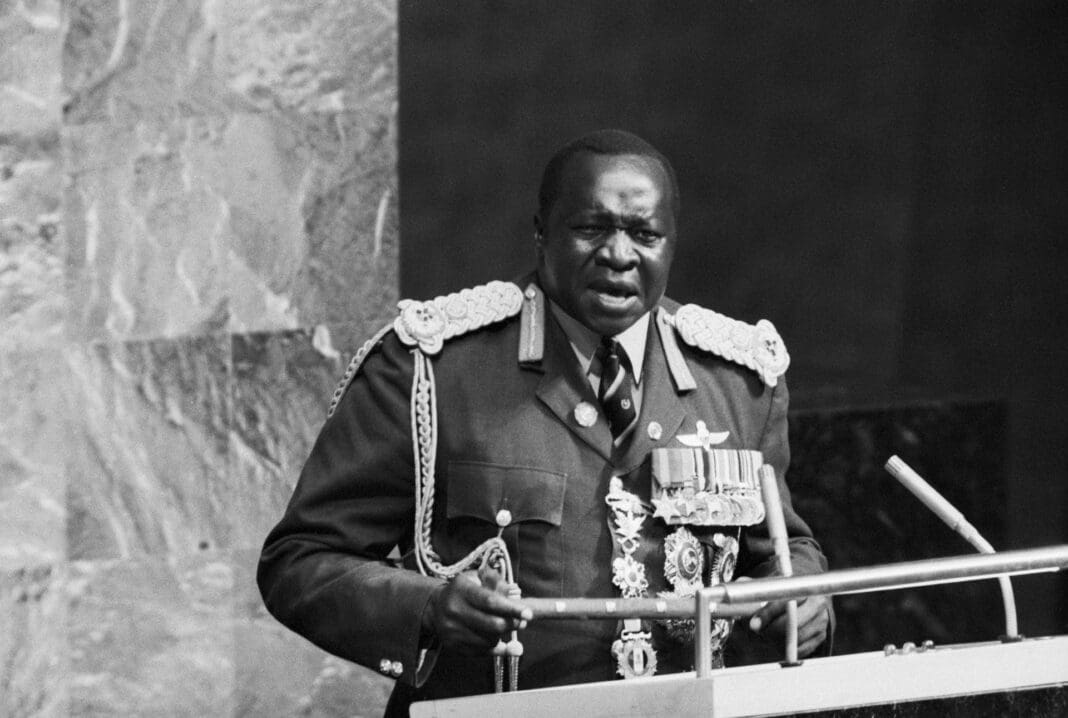

Fifty years ago, Ugandan President Idi Amin wrote to the governments of the British Commonwealth with a bold suggestion: Allow him to take over as head of the organization, replacing Queen Elizabeth II.

After all, Amin reasoned, a collapsing economy had made the U.K. unable to maintain its leadership. Moreover the “British empire does not now exist following the complete decolonization of Britain’s former overseas territories.”

It wasn’t Amin’s only attempt to reshape the international order. Around the same time, he called for the United Nations headquarters to be moved to Uganda’s capital, Kampala, touting its location at “the heart of the world between the continents of America, Asia, Australia and the North and South Poles.”

Amin’s diplomacy aimed to place Kampala at the center of a postcolonial world. In my new book, “A Popular History of Idi Amin’s Uganda,” I show that Amin’s government made Uganda – a remote, landlocked nation – look like a frontline state in the global war against racism, apartheid and imperialism.

Doing so was, for the Amin regime, a way of claiming a morally essential role: liberator of Africa’s hitherto oppressed people. It helped inflate his image both at home and abroad, allowing him to maintain his rule for eight calamitous years, from 1971 to 1979.

Amin was the creator of a myth that was both manifestly untrue and extraordinarily compelling: that his violent, dysfunctional regime was actually engaged in freeing people from foreign oppressors.

The question of Scottish independence was one of his enduring concerns. The “people of Scotland are tired of being exploited by the English,” wrote Amin in a 1974 telegram to United Nations Secretary General Kurt Waldheim. “Scotland was once an independent country, happy, well governed and administered with peace and prosperity,” but under the British government, “England has thrived on the energies and brains of the Scottish people.”

Even his cruelest policies were framed as if they were liberatory. In August 1972, Amin announced the summary expulsion of Uganda’s Asian community. Some 50,000 people, many of whom had lived in Uganda for generations, were given a bare three months to tie up their affairs and leave the country. Amin named this the “Economic War.”

In the speech that announced the expulsions, Amin argued that “the Ugandan Africans have been enslaved economically since the time of the colonialists.” The Economic War was meant to “emancipate the Uganda Africans of this republic.”

“This is the day of salvation for the Ugandan Africans,” he said. By the end of 1972, some 5,655 farms, ranches and estates had been vacated by the departed Asian community, and Black African proprietors were queuing up to take over Asian-run businesses.

A year later, when Amin attended the Organization of African Unity summit in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, his “achievements” were reported in a booklet published by the Uganda government. During his speech, Amin was “interrupted by thunderous applauses of acclamation and cheers, almost word for word, by Heads of State and Government and by everybody else who had a chance to hear it,” according to the the report.

It was, wrote the government propagandist, “very clear that Uganda had emerged as the forefront of a True African State. It was clear that African nationalism had been born again. It was clear that the speech had brought new life to the freedom struggle in Africa.”

Amin’s policies were disastrous for all Ugandans, African and Asian alike. Yet his war of economic liberation was, for a time, a source of inspiration for activists around the world. Among the many people gripped by enthusiasm for Amin’s regime was Roy Innis, the Black American leader of the civil rights organization Congress of Racial Equality.

In March 1973, Innis visited Uganda at Amin’s invitation. Innis and his colleagues had been pressing African governments to grant dual citizenship to Black Americans, just as Jewish Americans could earn citizenship from the state of Israel.

Over the course of their 18 days in Uganda, the visiting Americans were shuttled around the country in Amin’s helicopter. Everywhere, Innis spoke with enthusiasm about Amin’s accomplishments. In a poem published in the pro-government Voice of Uganda around the time of his visit, Innis wrote:

“Before, the life of your people was a complete bore,

And they were poor, oppressed, exploited and economically sore.

And you then came and opened new, dynamic economic pages.

And showered progress on your people in realistic stages.

In such expert moves that baffled even the great sages,

your electric personality pronounced the imperialists’ doom.

Your pragmatism has given Ugandans their economic boom.”

In May 1973, Innis was back in Uganda, promising to recruit a contingent of 500 African American professors and technicians to serve in Uganda. Amin offered them free passage to Uganda, free housing and free hospital care for themselves and their families. The American weekly magazine Jet predicted that Uganda was soon to become an “African Israel,” a model nation upheld by the energies and knowledge of Black Americans.

As some have observed, Innis was surely naive. But his enthusiasm was shared by a great many people, not least a great many Ugandans. Inspired by Amin’s promises, their energy and commitment kept institutions functioning in a time of great disruption. They built roads and stadiums, constructed national monuments and underwrote the running costs of government ministries.

Their ambitions were soon foreclosed by a rising tide of political dysfunction. Amin’s regime came to a violent end in 1979, when he was ousted by the invading army of Tanzania and fled Uganda.

But his brand of demagoguery lives on. Today a new generation of demagogues claim to be fighting to liberate aggrieved majorities from outsiders’ control.

In the 1970s, Amin enlisted Black Ugandans to battle against racial minorities who were said to dominate the economy and public life. Today an ascendant right wing encourages aggrieved white Americans to regard themselves as a majority dispossessed of their inheritance by greedy immigrants.

Amin encouraged Ugandans to regard themselves as frontline soldiers, engaged in a globally consequential war against foreigners. In today’s America, some people similarly feel themselves deputized to take matters of state into their own hands. In January 2021, for instance, a right-wing group called “Stop the Steal” organized a rally in Washington. Vowing to “take our country back,” they stormed the Capitol building.

The racialized demagoguery that Idi Amin promoted inspired the imagination of a great many people. It also fed violent campaigns to repossess a stolen inheritance, to reclaim properties that ought, in the view of the aggrieved majority, to belong to native sons and daughters. His regime is for us today a warning about the compelling power of demagoguery to shape people’s sense of purpose.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Derek R. Peterson, University of Michigan

Read more: Idi Amin and Donald Trump – strong men with unlikely parallels Idi Amin’s ‘economic war’ victimised Uganda’s Africans and Asians alike Zohran Mamdani’s last name reflects centuries of intercontinental trade, migration and cultural exchange

Derek R. Peterson receives funding from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the Andrew Mellon Foundation.