Imagine a grand house on a hill, after dark on an autumn night. As the door opens, an organ pierces through the thick silence and echoes through the cavernous halls.

The tune that comes to many minds will be Johann Sebastian Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565, an organ work composed in the early 18th century. Most people today recognize it as a sonic icon of a certain type of fear: haunting and archaic, the kind of thing likely to be manufactured by someone – a ghost, perhaps – wearing a tuxedo and lurking in an abandoned mansion.

Bach could not have thought that his nearly 9-minute organ piece would become so strongly associated with haunted houses and sinister machinations. As a musicologist whose current research is focused on the musical representation of mystery, I see the story of this song as a classic example of how the meaning, use and purpose of music can change over time.

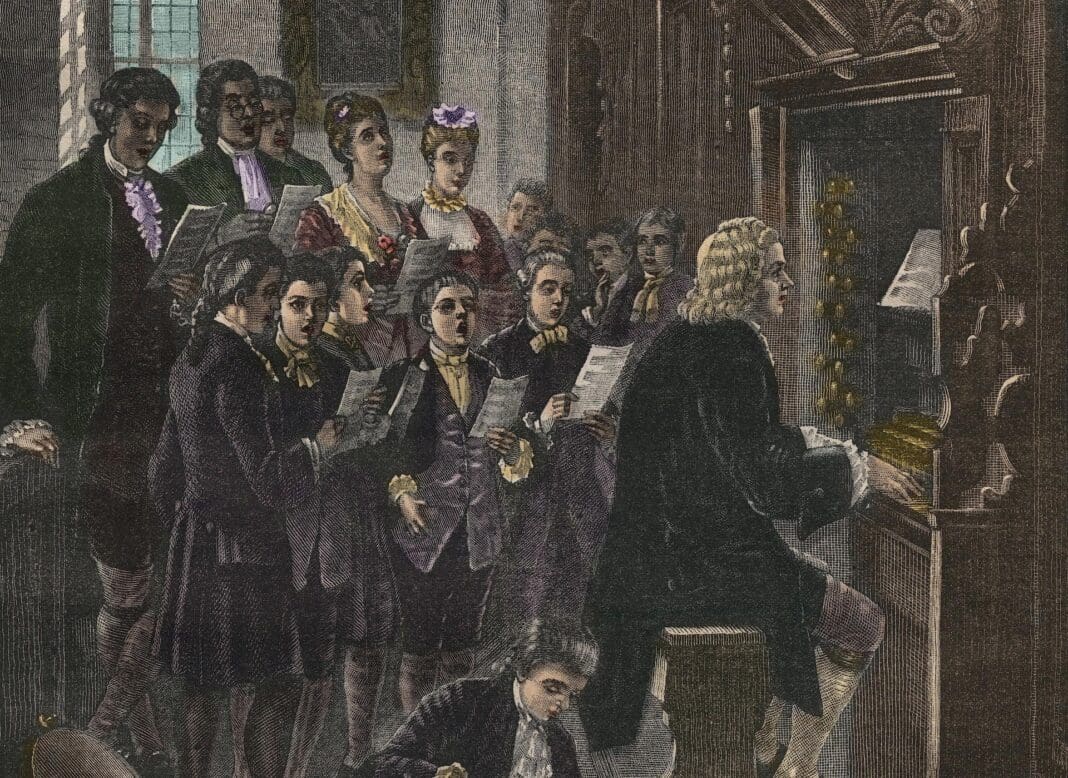

Bach was a technically skilled musical craftsman and a scholar of composition. In his work, he sought to dutifully serve his employer, whether that was a Lutheran church, a royal court or a town council. He wasn’t like the famous composers of later eras – Mozart, Haydn, Liszt – who used their talents to build fame and increase their influence.

As Bach scholar Christoph Wolff has pointed out, Toccata and Fugue belongs to the repertory of virtuosic show pieces that Bach created to exhibit his own prowess as an organ player.

For Bach, who left no documents pertaining to this piece, the work would have been merely functional, a way to show the abilities of the organ and to put his talent to good use – not indicative of emotions, stories or other ideas.

The music of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue owes much of its spookiness to the drama it employs: Harmonically, it is set in a somber minor mode that is generally aligned with more negative emotions such as sadness, nostalgia, loss and despair.

Within this minor mode, a striking melodic contour is unleashed. The piece’s first pitch is the fifth scale degree instead of the first pitch of the scale. This means that from the first note there is some uncertainty: because of the unexpected note. Then there’s a quick descent down the D minor scale after the initial flickering ornament.

Add to this the silent background and the pregnant pauses between musical phrases, and the first 30 seconds are sheer suspense. A heavily contrasting texture – with lots of notes stacked up on each other – follows, introducing sonic clashes and rich harmony that swell with power.

The piece moves quickly after this arresting beginning, relentlessly following a pattern of solo figures interspersed with massive, pounding chords.

The sounds of the pipe organ further enhance the piece’s spooky sound.

During the Baroque era – roughly 1600 to 1750 – the organ reached the height of its popularity. At the time, it was one of humankind’s most technologically advanced instruments, and musicians routinely performed organ music during church services and in concerts held at churches.

But as musicologist Edmond Johnson has explained, many instruments preferred in the Baroque era, such as the organ and the harpsichord, had become out of fashion by the 19th century, stashed in storage rooms where they gathered dust.

When music historians and ancient music revivalists first brought these instruments out for public performances after more than a century in storage, the now unfamiliar instruments sounded archaic and creaky to audiences.

Musicologist Carolyn Abbate has argued that music can be “sticky,” collecting new meanings as contexts change and time passes. You can see this in the way Schubert’s famous “Ave Maria” – originally written as accompaniment to the words of Walter Scott’s poem “Lady of the Lake” – became associated with Catholic devotional music. Or the way Tchaikovsky’s “The Nutcracker” morphed from an underappreciated neo-Romantic ballet in 19th-century Russia to a popular annual Christmas tradition in the U.S.

So how did the piece become associated with Halloween?

One landmark film likely contributed to the impression that Bach’s Toccata and Fugue portends something nefarious: the 1931 release of “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” Rouben Mamoulian’s famous adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel uses Bach’s Toccata in the opening credits.

The piece sets a tone of suspense and suggests the depths of evil that Dr. Jekyll will encounter in his experiments. In the film, Dr. Jekyll is portrayed as an amateur organist who enjoys playing Bach’s music, so it is easy for a listener to apply the dramatic, suspenseful and complex nature of the Toccata to Dr. Jekyll and his alter ego.

Since then, the music has also been used in other spooky films and video games, including “The Black Cat” (1934) and the “Dark Castle” video game series.

Though Bach himself would not have thought of Toccata and Fugue in D minor as spooky, its origins as an innocuous concert piece won’t prevent it from sending a shiver down people’s spines every Halloween.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.

Read more: The humble origins of ‘Silent Night’ How the sounds of ‘Succession’ shred the grandeur and respect the characters so desperately try to project

Megan Sarno does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.