The Bible story of the Good Samaritan is more than a mainstay of Sunday school courses. “Good samaritan” is the catch-all way to describe a do-gooder – someone who stops to change the tire of a stranded motorist, helps a lost child find their parents in a store and gives money to disaster relief programs.

But as an ethicist, I’d argue that the parable’s moral vision is much more radical than merely advising people to help out when they can. The parable raises profound philosophical questions about what it means to love another person, and our sometimes astonishing capacity to feel connected to others.

The parable of the Good Samaritan occurs in the Gospel of Luke, in a part of the Bible where Jesus is attracting followers and preparing them to spread his movement.

During one of these sessions, a religious scholar asks him to explain the fundamental commandment in Jewish ethics: “You will love God with all of your heart, all of your mind, and all of your strength. And you will love your neighbor as yourself.” In response, Jesus tells the now-iconic story:

One time a man was traveling down the dangerous road from Jerusalem to Jericho. The Bible describes absolutely nothing else about this man, but the tradition assumes he is Jewish. The man was attacked and beaten within an inch of his life. As he lay in a ditch, a temple priest and a temple functionary both noticed him but hurried past.

Then a member of another tribe, a Samaritan, saw him. The Samaritan was immediately moved and rushed over, hoisted the man onto his donkey, took him to a nearby inn and stayed up with him all night, nursing him back to life. The next morning he paid the innkeeper two denarii – Roman silver coins, about two days’ salary – and offered to pay the tab for anything else the man might require as he recuperated.

Jesus turns the question back to the scholar: Who loved their neighbor? The scholar concedes the point – the Samaritan who had mercy.

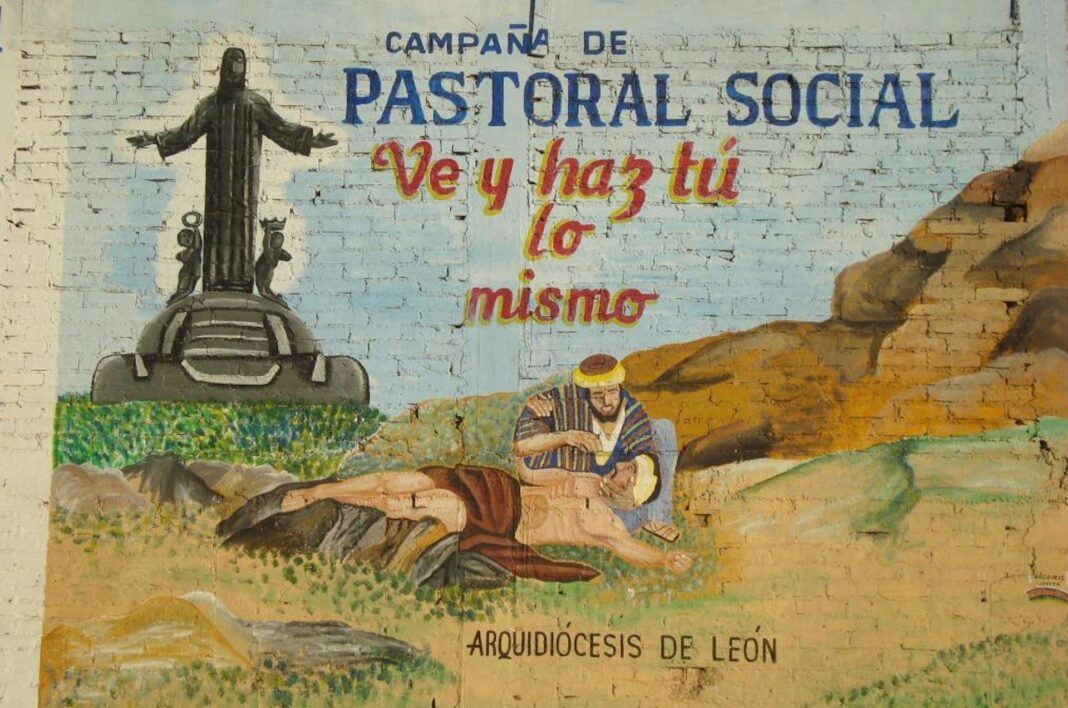

“Go and do likewise,” Jesus replies.

What exactly did the Samaritan do that reveals the core of the love ethic? Jesus says specifically that the Samaritan’s “guts churned” when he saw the man in need: the Greek word used in the text is “splagchnizomai.”

The term occurs in other places in the Gospels, as well, evoking a very physical kind of emotional response. This “gut-wrenching love” is spontaneous and visceral.

Ancient philosophers spent plenty of time trying to understand the ways humans love, often using highly intellectual frames. “The Symposium,” a dialogue by Plato, depicts Socrates drunkenly debating the essence of erotic love with his friends. Aristotle beautifully theorizes about friendship, “philia,” in his teachings about ethics. He introduces the idea that when we truly love a friend, we think of them as our “second self” – the lives of your closest friends become entangled within your own.

Many of the early Christian philosophers debated the nature of “agape,” the Greek word the New Testament uses to describe the selfless, unconditional love that characterizes the very nature of God. Saint Augustine introduced the concept of “amoris ordo,” the order of loves: that morality compels someone to first love the highest good, which is God, and then organize the rest of their loves to serve this highest love.

These concepts present love as an intellectual attitude that is often reserved for a select group, such as God, or one’s family, or one’s countrymen. And Christian notions of “agape” specifically put love just out of reach, only possible for a divine being, though humans should aspire to it and can experience its effects.

Splagchnizomai is different – such a physical emotion is only possible for creatures like us, with bodies. And as the parable of the Good Samaritan shows, it is an emotion that can be triggered by anyone, at any time, if we are – like the Samaritan – ready to be so moved.

Much like their ancient counterparts, philosophers of the past century have struggled to explain how love can be one of the most morally significant elements of our lives, while also being so extraordinarily partial, biased and seemingly arbitrary.

To resolve the tension, many treat love not as a source of insight but as a messy feature of human psychology – an impediment that ethical reasoning must navigate around.

Indeed, the most prominent recent movements in applied ethics are wholly oriented around rational efficiency. The Effective Altruism movement argues that people should use evidence to transform themselves into the most efficient do-gooders they can possibly be. Proponents discourage college graduates looking to make a difference from pursuing public service and recommend high-paying jobs instead, arguing that they can have a bigger impact giving away wealth than directly caring for others. Emotions are viewed with suspicion, as sources of potential bias – not sources of moral wisdom.

In the book “Against Empathy,” psychologist Paul Bloom warns that such emotions “do poorly in a world where there are many people in need and where the effects of one’s actions are diffuse, often delayed, and difficult to compute.”

Compare that to the parable of the Good Samaritan, which portrays ethics as an emotional, deeply personal and almost absurdly inefficient matter. Those two denarii were a weighty sum – they could have been used to beef up security on the road and prevent other robberies, rather than save a single man. Nor did the Samaritan off-load the injured man onto a local healer. He cared for him directly, the way someone might sit with a gravely ill family member.

In Jesus’ time, as in our own, there was significant debate about how to understand the commandments to love one’s neighbor. One school of thought considered a “neighbor” to be a member of your community: The Book of Leviticus says not to hold grudges against fellow countrymen. Another school held that you were obligated to love even strangers who are only temporarily traveling in your land. Leviticus also declares that “The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as one of your citizens; you shall love him as yourself.”

In the story of the Good Samaritan, Jesus seems to come down on the side of the broadest possible application of the love ethic. And by emphasizing a particular type of love – the gut-wrenching kind – Jesus seems to indicate that the way of progress in ethics is through emotions, rather than around them.

My current work focuses on the upshots of reading this parable as a philosophical guide to ethics in our own time. For instance, if the love ethic is right, preparing students to make progress on complex social issues requires more than cost-benefit analysis. It also requires helping them to recognize and cultivate emotions, especially loving compassion.

There are clear parallels between the original parable of the good Samaritan and pressing political issues today, especially migration – and also, I believe, polarization. His story calls closer attention to humans’ innate capacity to love beyond the limits of familiar relationships or “tribes” – and just how much is lost when we do not.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Meghan Sullivan, University of Notre Dame

Read more: St. Thomas Aquinas’ skull just went on tour − here’s what the medieval saint himself would have said about its veneration In asking Trump to show mercy, Bishop Budde continues a long tradition of Christian leaders ‘speaking truth to power’ What is love? A philosopher explains it’s not a choice or a feeling − it’s a practice

Meghan Sullivan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.