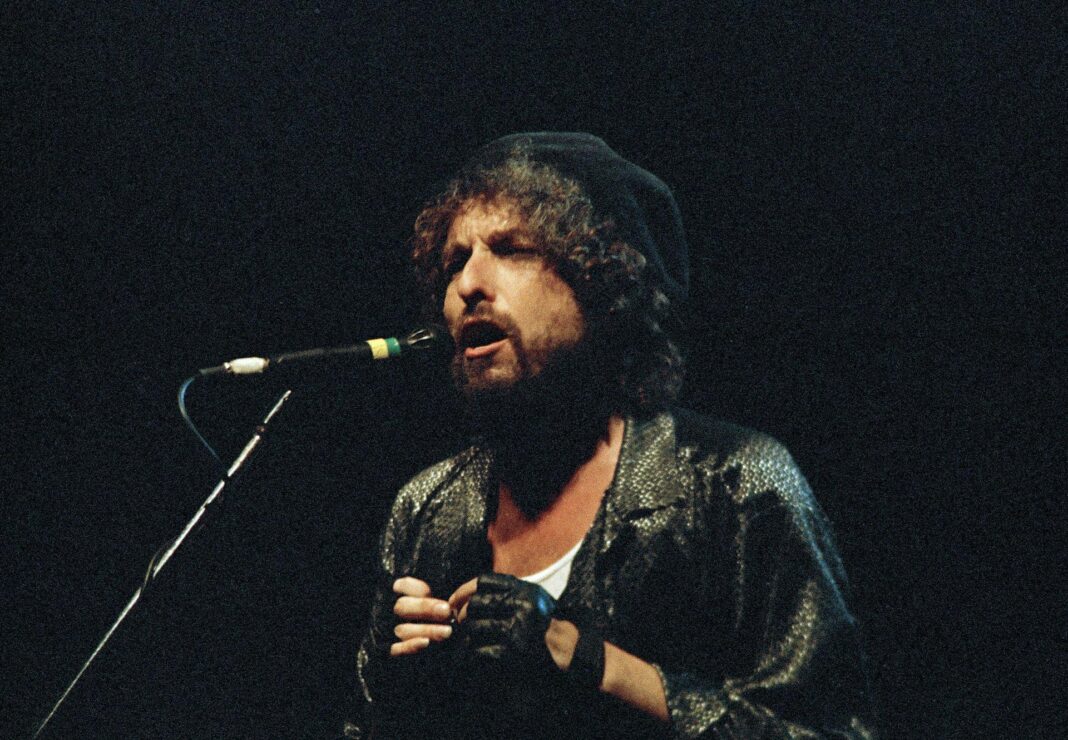

James Mangold’s film “A Complete Unknown,” nominated for eight Oscars, captures the elusive, enigmatic quality of Bob Dylan in the early 1960s: the years he emerged as a major musical and cultural phenomenon. A scant few years after he came to New York from Minnesota, and legally changed his name from Robert Allen Zimmerman, Dylan transformed American music.

Especially “unknown” and baffling is Dylan’s religious and spiritual identity, one that has undergone many transformations. Mangold’s film avoids these questions, as does his 2005 film “Walk the Line,” a Johnny Cash biopic. The filmmaker – and much of Hollywood in general – must believe religion isn’t good at the box office.

As a music fan and scholar of religion, I have long been interested in artists’ religious backgrounds. Cash’s tumultuous life, like his friend and collaborator Dylan’s, was rich in religious affiliations and commitments.

And both of these musical giants shared a connection with Israel, defying calls to cancel performances there over concern for Palestinian rights – similar to artists’ debates in recent years. Dylan’s, in particular, is difficult to parse and part of his larger spiritual journey – one that’s rambled through Judaism and Christianity and back again.

The last time Dylan took the stage in Israel was at Tel Aviv’s Ramat Gan Stadium in June 2011. It had been 18 years since his last performance in the country, though he had made many personal visits in the interim.

He was, of course, a household name in Israel, revered by the young as well as the not so young. The audience members that evening, according to the Haaretz reporter who covered the event, were “overwhelmingly young, overwhelmingly native-born Israelis.”

Surely everyone in attendance knew that Dylan had been born Robert Zimmerman – indeed, that he had a long, complicated relationship with Israel and with Judaism itself.

Young Zimmerman grew up in Hibbing, Minnesota, in a home that emphasized Jewish identity, if not its religious rituals. A visiting Orthodox rabbi had prepared him for his bar mitzvah, which took place in May 1954, with 400 guests in attendance. That summer, Zimmerman attended Camp Herzl in Wisconsin, a Jewish camp with a Zionist orientation; he would return there the following summers as well. At Camp Herzl young Bob formed his first musical group, the Jokers.

In his mid-20s, he married Sara Lownds, a Jewish woman with whom he had five children. Dylan made his first private visit to Israel in 1969 and returned regularly in the early 1970s. In May 1971, he celebrated his 30th birthday in Jerusalem; photos of him at the Western Wall appeared in Israeli and American newspapers, fueling speculation that he had “found religion” in the holy city.

In some ways, the young star put distance between himself and his Jewish roots – he was now Dylan, after all, not Zimmerman. But even in these early years, as throughout his career, “Dylanologists” delighted in the biblical allusions in some of his songs – including irreverent ones, at least at first glance.

“Highway 61 Revised,” for example, the title track of a 1965 album, kicks off with the binding of Isaac: a section of the Book of Genesis where God famously tests Abraham with a command – reprieved at the last moment – to kill his beloved child:

But Dylan confounded both his admirers and his critics, turning abruptly in the late 1970s to evangelical Christianity. After his conversion, Dylan took a course at Vineyard Christian Fellowship in Los Angeles, which emphasized the end-time narratives of the New Testament Book of Revelation.

His years as a born-again Christian resulted in a series of gospel-influenced albums and at least one more visit to Israel during this early ’80s period. In 1987 he gave his first concerts there, kicking off his Temples in Flames world tour alongside Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers.

Within years of embracing Christianity, however, Dylan’s spiritual life yet again confounded his critics and fans, including the more scholarly obsessives known as “Dylanologists.” Born into Judaism, then a born-again evangelical, the rocker now forged ties to Chabad, an ultra-Orthodox Hasidic Jewish movement. Between 1986 and 1991, he made three appearances on the Chabad “To Life” Telethon, an annual fundraiser broadcast from Los Angeles.

Because Dylan was – and is – so private and publicity-shy, it is difficult to know whether such ecumenism represented true spiritual seeking, a political statement or sheer mischief.

Whether he was presenting himself as a born-again Christian, a supporter of Chabad or just a rock and roller, Dylan seemed inextricably connected to Israel in all its complexity. For example, many listeners interpreted the song “Neighborhood Bully” on his 1983 “Infidels” album as a “declaration of full-throated Israel support,” as Haaretz wrote.

The lyrics presented the title character, the “bully,” as an unrepentant, besieged victim: “His enemies say he’s on their land/ They got him outnumbered a million to one/ He got no place to escape to, no place to run.”

Dylan performed again in Israel in June 1993, bringing his summer tour to Tel Aviv, Beersheba and Haifa.

It would be nearly two decades before his next public performance in Israel, the 2011 concert at Ramat Gan. By then, performing in Israel had become much more controversial, with artists planning to tour there under scrutiny.

The boycott, divestment and sanctions movement publicly pressured the singer to cancel his Tel Aviv show, appealing to his past support of the American Civil Rights Movement. Activists called on Dylan “not to perform in Israel until it respects Palestinian human rights. A performance in Israel, today, is a vote of support for its policies of oppression, whether you intend for it to be that, or not.”

Ever the enigmatic artist, Dylan did not respond to the BDS appeal, nor did he cancel his concert. The towering pop-music icon did not say why. But many Israelis and Americans read his return as a gesture of support for the Jewish state in the face of widespread criticism.

Tel Aviv welcomed him with open arms, including a television news profile of his life, music and Jewish affiliations. Though he said nothing from the stage during the performance – late-career Dylan is notorious for not addressing the audience between songs – Israeli fans saw the concert as a triumphant homecoming.

“Dylan lives here. He lives in the culture of Israel,” wrote the Haaretz reviewer. “He has influenced Israel for the better more than any other American Jew.”

Since the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war in 2023, international criticism of Israeli policies has become much more strident. Dylan, as cryptic as ever, has neither joined the critics nor identified himself with Israel’s supporters.

But supporters are posting “Neighborhood Bully” wherever and whenever they can.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Shalom Goldman, Middlebury

Read more: Bob Dylan and the creative leap that transformed modern music How Bob Dylan used the ancient practice of ‘imitatio’ to craft some of the most original songs of his time Is it time to retire the ‘Arab-Israeli conflict’? Hostilities now extend beyond those boundaries

Shalom Goldman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.