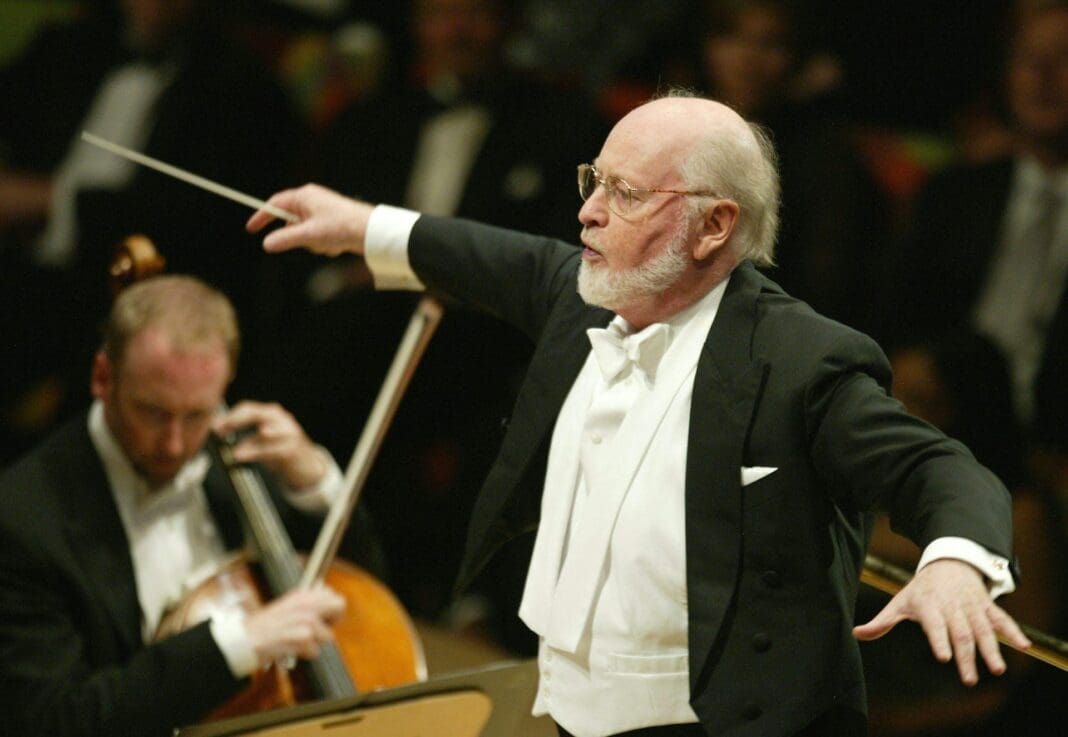

When Harrison Ford saddles up once again in “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny,” he has an invisible partner along for the ride: composer John Williams, who received his 54th Academy Award nomination for scoring the movie.

Reviews are mixed, but as one critic writes, “When Indy and Helena (his goddaughter) get to actual treasure-hunting, and John Williams’ all-timer theme kicks in again, the movie clicks.”

At 92, Williams is the oldest Oscar nominee in Academy history – for the second time. The first time was in 2023, when his score to “The Fabelmans” was nominated. Altogether, Williams has been nominated for more Oscars than anyone in movie history except Walt Disney and has won five.

Williams began working in television and film in the 1950s, first as a studio pianist and then as a composer for television and feature films. But it wasn’t until his music for 1975’s “Jaws,” with its ominous two-note motif, that he left his indelible stamp on Hollywood.

When Williams’ music for “Star Wars” poured out of cinema sound systems two years later, he single-handedly made the symphonic movie score respectable again, after a decade of rock ’n’ roll compilations and quirky uses of regional material with limited instrumentation. If “Star Wars” hadn’t been a blockbuster, movies might never have returned to the use of big orchestras, which were standard from the advent of synchronized sound in 1927’s “The Jazz Singer” into the 1960s.

I am a music professor, composer of orchestral works and lifelong student of film music. My admiration for John Williams has only deepened as he has continued to produce greatness.

Whether it’s disaster films like “The Poseidon Adventure,” blockbusters such as the first three “Harry Potter” films or stirring dramas like “Schindler’s List,” Williams continues to prove that he can do it all, regardless of genre. His film scores owe much to his deep background in every aspect of music, from a young age.

After a stint in the Air Force, during which he wrote his first film score, for a travelogue about Newfoundland, Williams studied at the Juilliard School and the Eastman School of Music. In 1956 he returned to Los Angeles, where he had once led dance bands as a high schooler under the name “Little Johnny Love.”

He quickly found work as a film studio pianist and came to the attention of renowned Hollywood composer Henry Mancini. Credited as Johnny Williams, he performed the iconic bass line ostinato – meaning “obstinate” in Italian – for Mancini’s theme for the television detective classic “Peter Gunn.”

Williams became a sought-after studio keyboardist, playing on the film soundtracks for hits such as “West Side Story.” He augmented this work by arranging and orchestrating odd bits of music here and there for television and movies.

His first scores were for television shows such as “Playhouse 90,” “Bachelor Father” and the pilot episode of “Gilligan’s Island.” Williams worked with producer Irwin Allen on shows such as “Lost in Space” and “Land of the Giants.” His first feature film score was for 1958’s “Daddy-O.”

For Williams’ score for “Star Wars” and many subsequent films, he conducted the London Symphony Orchestra. “Star Wars” reached the Billboard Top 10 in 1977 on both the Hot 100 and adult contemporary charts – an extraordinary crossover feat that has never been repeated.

His work on “Star Wars” showed that what amounted to an orchestral suite based on the score could sell extremely well as a soundtrack album. This made Williams an important source of revenue for a film, and a highly valued collaborator.

But it was his score for longtime associate Steven Spielberg’s 1982 hit film “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial” that was Williams’ first score to be embraced by concert orchestras. It introduced audiences to his other side, as a composer of serious concert music.

The suite from “E.T.” was frequently performed by orchestras across the country, to great acclaim. Orchestral demand for Williams’ music rose to such a level that his career as a classical musician became almost as fruitful as his work with film music. Williams’ scores not only moved audiences but also provided each member of the orchestra a meaningful and satisfactory playing experience, thus increasing his appeal to performers of his music.

The “E.T.” music also soars, literally, on film. The scoring of the finale, in which protagonist Elliott and his friends help the alien escape captivity and return to his home planet, is so effective that Spielberg re-cut the end of the film to match Williams’ music, inverting the normal relationship between director and composer.

Williams has written concertos for almost every instrument, including one for superstar cellist Yo-Yo Ma; two symphonies and a sinfonietta for wind instruments; and a chamber quartet incorporating the Shaker song “Simple Gifts” for President Barack Obama’s 2008 inauguration. He is emeritus conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra, which he led from 1980 to 1993, succeeding the legendary Arthur Fiedler.

Williams’ classical education and abilities have played a huge role in the sound and success of his movie scores. George Lucas had reportedly entertained the idea of using classic works for his “Star Wars” soundtrack. Williams successfully argued in favor of an original score, but one that suggested old-Hollywood atmosphere.

His music for “Star Wars” draws equally from the romantic-style work of European film-score pioneers like Max Steiner and Erich Korngold; the operatic and leitmotif technique of Richard Wagner; and the lush and entrancing orchestration of Igor Stravinsky. All of the “Star Wars” film scores also are informed, as much of his music is, by Williams’ work in jazz and popular music.

Many of Williams’ film scores have become icons of popular culture. The American Film Institute ranks the score to “Star Wars” as the greatest film score of all time, and the Library of Congress has entered its recording into the National Recording Registry, citing its cultural, historical and aesthetic significance.

Williams has been nominated for 76 Grammy Awards and won 26, most recently in 2024 for the “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny” score. He has received numerous career honors, including the National Medal of Arts in 2009. But I believe a different honor most exemplifies his illustrious career.

In 2022, Williams received an honorary knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II, one of the final awards the queen approved before her death. Perhaps a fitting title, cinematic as it is, for a life lived so fully and so creatively: The Last Knight.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and analysis to help you make sense of our complex world.

Read more: How the sounds of ‘Succession’ shred the grandeur and respect the characters so desperately try to project Music inspires powerful emotions on screen, just like in real life

Arthur Gottschalk is a member of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers.