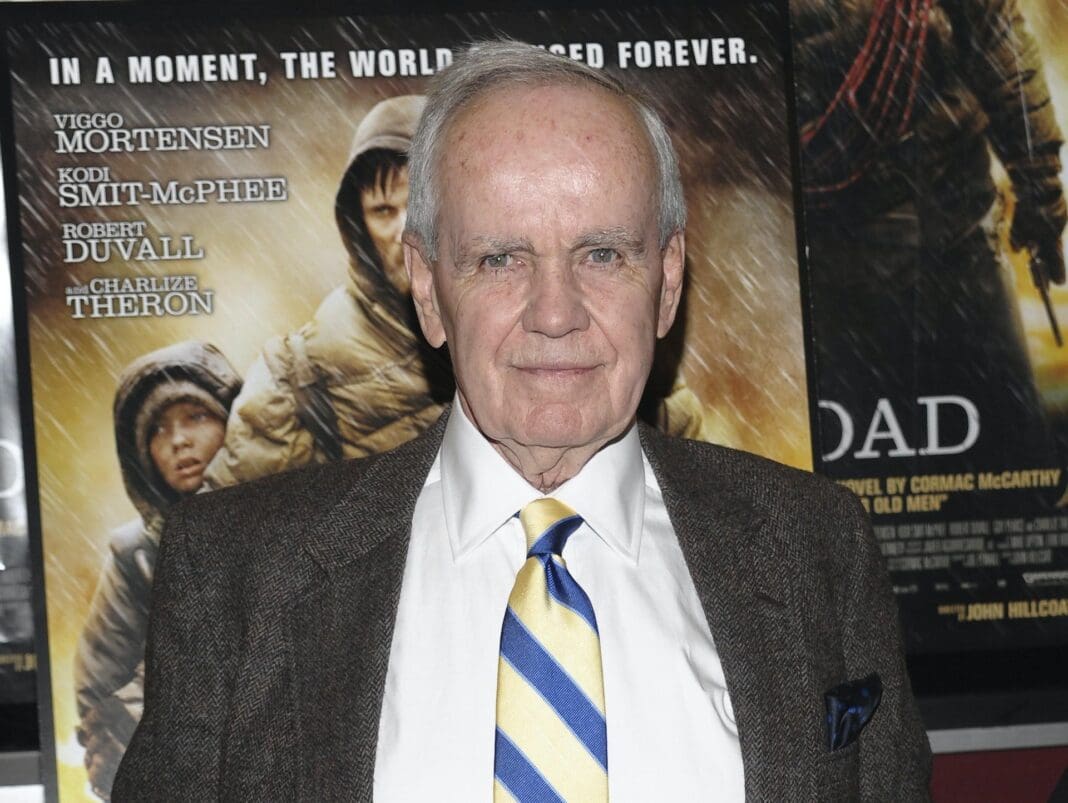

Cormac McCarthy, who died on June 13, 2023, at the age of 89, is often characterized rather narrowly as a Southern writer, or perhaps a Southern Gothic writer.

McCarthy did lean heavily on his Tennessee upbringing in his first four novels, and he set many others in the deserts of the Southwest U.S. However, as a writer, he saw himself as a part of an expansive literary community, one that stretched back to the classical and Elizabethan periods, and one that drew on a variety of genres, cultures and influences.

His unique and varying writing style has been compared with that of many of the greatest authors of American letters, with scholars highlighting connections to the writings of Herman Melville, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Toni Morrison, Thomas Pynchon, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Flannery O’Connor and William Faulkner.

As such an unwieldy list of compatriots suggests, McCarthy is an author who experimented with language and literary technique. Each of his books typically departs radically in tone, structure and prose from the previous one.

I’m currently working on a book that’s tentatively titled “How Cormac Works: McCarthy, Language, and Style.” In it, I trace McCarthy’s career-long commitment to playing with style, particularly his approach to narration and his techniques for conveying a mood.

Depending on the book – and even passages within certain books – McCarthy’s writing can be characterized as minimalistic, meandering, esoteric, humorous, terrifying, pretentious, sentimental or folksy.

Some novels depend heavily on dense passages of narrative exposition and philosophizing, while others lean heavily on everyday dialogue. Some books celebrate regional voices and vernacular, and others adopt a neutral, removed and clinical tone.

It is possible to see McCarthy’s literary range and stylistic experimentation in two of his most famous novels, “Blood Meridian,” which came out in 1985, and “The Road,” which was published over two decades later, in 2006, and was turned into a movie in 2009.

In “Blood Meridian,” set in the desert of the Southwest U.S. and Mexico, McCarthy’s prose is dense, with details piling up one after another.

Take the famous scene in which a mercenary gang of American scalp hunters encounters a band of Comanche warriors:

“A legion of horribles, hundreds in number, half naked or clad in costumes attic or biblical or wardrobed out of a fevered dream with the skins of animals and silk finery and pieces of uniform still tracked with the blood of prior owners, coats of slain dragoons, frogged and braided cavalry jackets, one in a stovepipe hat and one with an umbrella and one in white stockings and a bloodstained wedding veil and some in headgear or cranefeathers or rawhide helmets that bore the horns of bull or buffalo and one in a pigeontailed coat worn backwards and otherwise naked and one in the armor of a Spanish conquistador. … ”

The entire sentence is much too long to quote here. But you get the picture: There is very little punctuation and there are few places to even take a breath.

The narration in other moments of the novel catalogs the desert landscape of the U.S. West in similarly painstaking and tedious – if also beautiful – detail. The prose feels drawn out, slow and repetitive, like the subject of the novel: the United States’ western expansion in the 19th century, a campaign of escalating destruction that McCarthy characterizes in the novel as “some heliotropic plague.”

“The Road,” a later novel similarly committed to the idea of incessant movement, could not be more different in its style, pacing and rhythm. The prose in that novel, which won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for fiction, is concise and is marked by a linguistic restraint that’s entirely absent in “Blood Meridian.”

Rather than dense and overwhelming passages, this novel is constructed of short and distinct paragraphs that are separated by white space and often unrelated to what comes directly before or after:

It was colder. Nothing moved in that night world. A rich smell of woodsmoke hung over the road. He pushed the cart on through the snow. …

In his dream she was sick and he cared for her. The dream bore the look of sacrifice but he thought differently. …

On this road there are no godspoke men. They are gone and I am left and they have taken with them the world. Query: How does the never to be differ from what never was?

Dark of invisible moon. The nights now only slightly less black. …

People sitting on the sidewalk in the dawn half immolate and smoking in their clothes. Like failed sectarian suicides. …

Each paragraph in this passage is different in tone, subject matter, place, and time from what comes before and appears after.

It might be tempting to see such difference as an evolution, as McCarthy honing and taming his narrative voice from his earlier work. But his final long novel, “The Passenger,” which was published in 2022, returns again to the rambling prose reminiscent of McCarthy’s big novels in the middle of his career, “Suttree” and “Blood Meridian.”

Some readers find McCarthy’s stylistic flourishes and experimentation excessive – or, even worse, pretentious. But they always struck me as reflecting his love of words and the endless possibilities of language.

In a blurb that was originally written for McCarthy’s first novel, “The Orchard Keeper,” Ralph Ellison wrote, “McCarthy is a writer to be read, to be admired, and quite honestly – envied.”

As I learned of McCarthy’s death, I couldn’t help but think of this quote that marked the beginning of his career, and to think how right Ellison was to champion McCarthy’s craft – the careful use of language that sustained his work for six decades across 12 novels.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. The Conversation is trustworthy news from experts, from an independent nonprofit. Try our free newsletters.

Read more: Salman Rushdie wasn’t the first novelist to suffer an assassination attempt by someone who hadn’t read their book Philip Roth’s journey from ‘enemy of the Jews’ to great Jewish-American novelist

Bill Hardwig does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.