The Bob Dylan biopic “A Complete Unknown,” starring Timothée Chalamet, focuses on Dylan’s early 1960s transition from idiosyncratic singer of folk songs to internationally renowned singer-songwriter.

As a music historian, I’ve always respected one decision of Dylan’s in particular – one that kicked off the young artist’s most turbulent and significant period of creative activity.

Sixty years ago, on Halloween Night 1964, a 23-year-old Dylan took the stage at New York City’s Philharmonic Hall. He had become a star within the niche genre of revivalist folk music. But by 1964 Dylan was building a much larger fanbase through performing and recording his own songs.

Dylan presented a solo set, mixing material he had previously recorded with some new songs. Representatives from his label, Columbia Records, were on hand to record the concert, with the intent to release the live show as his fifth official album.

It would have been a logical successor to Dylan’s four other Columbia albums. With the exception of one track, “Corrina, Corrina,” those albums, taken together, featured exclusively solo acoustic performances.

But at the end of 1964, Columbia shelved the recording of the Philharmonic Hall concert. Dylan had decided that he wanted to make a different kind of music.

Two-and-a-half years earlier, Dylan, then just 20 years old, started earning acclaim within New York City’s folk music community. At the time, the folk music revival was taking place in cities across the country, but Manhattan’s Greenwich Village was the movement’s beating heart.

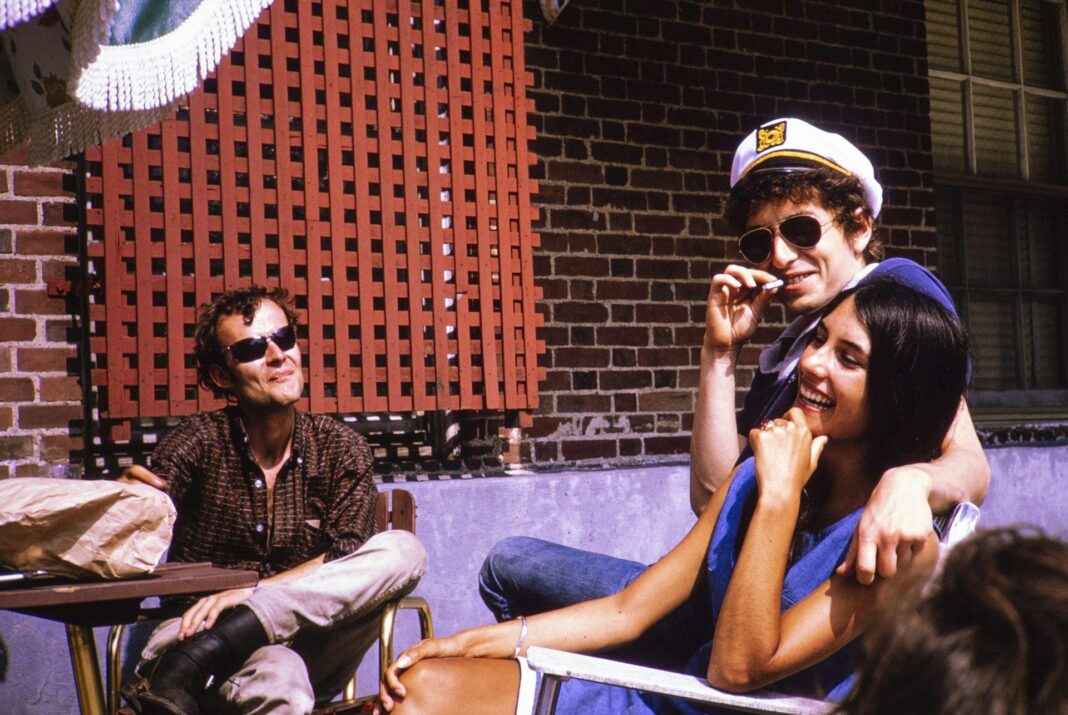

Mingling with and drawing inspiration from other folk musicians, Dylan, who had recently moved to Manhattan from Minnesota, secured his first gig at Gerde’s Folk City on April 11, 1961. Dylan appeared in various other Greenwich Village music clubs, performing folk songs, ballads and blues. He aspired to become, like his hero Woody Guthrie, a self-contained artist who could employ vocals, guitar and harmonica to interpret the musical heritage of “the old, weird America,” an adage coined by critic Greil Marcus to describe Dylan’s early repertoire, which was composed of material learned from prewar songbooks, records and musicians.

While Dylan’s versions of older songs were undeniably captivating, he later acknowledged that some of his peers in the early 1960s folk music scene – specifically, Mike Seeger – were better at replicating traditional instrumental and vocal styles.

Dylan, however, realized he had an unrivaled facility for writing and performing new songs.

In October 1961, veteran talent scout John Hammond signed Dylan to record for Columbia. His eponymous debut, released in March 1962, featured interpretations of traditional ballads and blues, with just two original compositions. That album sold only 5,000 copies, leading some Columbia officials to refer to the Dylan contract as “Hammond’s Folly.”

Flipping the formula of its predecessor, Dylan’s 1963 follow-up album, “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” offered 11 originals by Dylan and just two traditional songs. The powerful collection combined songs about relationships with original protest songs, including his breakthrough “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

“The Times They Are A-Changin’,” his third release, exclusively showcased Dylan’s own compositions.

Dylan’s creative output continued. As he testified in “Restless Farewell,” the closing track for “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” “My feet are now fast / and point away from the past.”

Released just six months after “The Times,” Dylan’s fourth Columbia album, “Another Side of Bob Dylan,” featured solo acoustic recordings of original songs that were lyrically adventurous and less focused on current events. As suggested in his song “My Back Pages,” he was now rejecting the notion that he could – or should – speak for his generation.

By the end of 1964, Dylan yearned to break away permanently from the constraints of the folk genre – and from the notion of “genre” altogether. He wanted to subvert the expectations of audiences and to rebel against music industry forces intent on pigeonholing him and his work.

The Philharmonic Hall concert went off without a hitch, but Dylan refused to let Columbia turn it into an album. The recording wouldn’t generate an official release for another four decades.

Instead, in January 1965, Dylan entered Columbia’s Studio A to record his fifth album, “Bringing It All Back Home.” But this time, he embraced the electric rock sound that had energized America in the wake of Beatlemania. That album introduced songs with stream-of-consciousness lyrics featuring surreal imagery, and on many of the songs Dylan performed with the accompaniment of a rock band.

“Bringing It All Back Home,” released in March 1965, set the tone for Dylan’s next two albums: “Highway 61 Revisited,” in August 1965, and “Blonde and Blonde,” in June 1966. Critics and fans have long considered these latter three albums – pulsing with what the singer-songwriter himself called “that thin, that wild mercury sound” – as among the greatest albums of the rock era.

On July 25, 1965, at the Newport Folk Festival, Dylan invited members of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band on stage to accompany three songs. Since the genre expectations for folk music during that era involved acoustic instrumentation, the audience was unprepared for Dylan’s loud performances. Some critics deemed the set an act of heresy, an affront to folk music propriety. The next year, Dylan embarked on a tour of the U.K., and an audience member at the Manchester stop infamously heckled him for abandoning folk music, crying out, “Judas!”

Yet the creative risks undertaken by Dylan during this period inspired countless other musicians: rock acts such as the Beatles, the Animals and the Byrds; pop acts such as Stevie Wonder, Johnny Rivers and Sonny and Cher; and country singers such as Johnny Cash.

Acknowledging the bar that Dylan’s songwriting set, Cash, in his liner notes to Dylan’s 1969 album “Nashville Skyline,” wrote, “Here-in is a hell of a poet.”

Enlivened by Dylan’s example, many musicians went on to experiment with their own sound and style, while artists across a range of genres would pay homage to Dylan through performing and recording his songs.

In 2016, Dylan received the Nobel Prize in literature “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” His early exploration of this tradition can be heard on his first four Columbia albums – records that laid the groundwork for Dylan’s august career.

Back in 1964, Dylan was the talk of Greenwich Village.

But now, because he never rested on his laurels, he’s the toast of the world.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Ted Olson, East Tennessee State University

Read more: Why Bruce Springsteen’s depression revelation matters How Bob Dylan used the ancient practice of ‘imitatio’ to craft some of the most original songs of his time In another newly discovered song, Woody Guthrie continues his assault on ‘Old Man Trump’

Ted Olson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.