In 1918, as World War I intensified overseas, the U.S. government embarked on a radical experiment: It quietly became the nation’s largest housing developer, designing and constructing more than 80 new communities across 26 states in just two years.

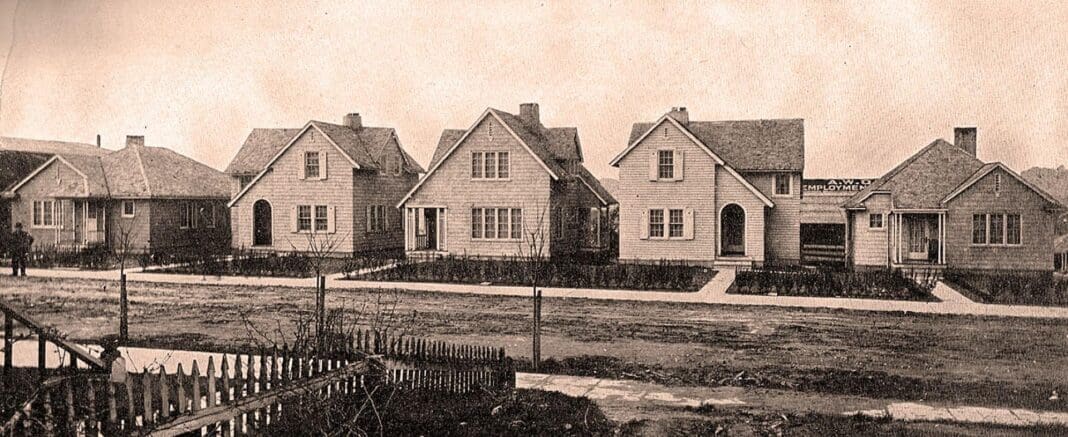

These weren’t hastily erected barracks or rows of identical homes. They were thoughtfully designed neighborhoods, complete with parks, schools, shops and sewer systems.

In just two years, this federal initiative provided housing for almost 100,000 people.

Few Americans are aware that such an ambitious and comprehensive public housing effort ever took place. Many of the homes are still standing today.

But as an urban planning scholar, I believe that this brief historic moment – spearheaded by a shuttered agency called the United States Housing Corporation – offers a revealing lesson on what government-led planning can achieve during a time of national need.

When the U.S. declared war against Germany in April 1917, federal authorities immediately realized that ship, vehicle and arms manufacturing would be at the heart of the war effort. To meet demand, there needed to be sufficient worker housing near shipyards, munitions plants and steel factories.

So on May 16, 1918, Congress authorized President Woodrow Wilson to provide housing and infrastructure for industrial workers vital to national defense. By July, it had appropriated US$100 million – approximately $2.3 billion today – for the effort, with Secretary of Labor William B. Wilson tasked with overseeing it via the U.S. Housing Corporation.

Over the course of two years, the agency designed and planned over 80 housing projects. Some developments were small, consisting of a few dozen dwellings. Others approached the size of entire new towns.

For example, Cradock, near Norfolk, Virginia, was planned on a 310-acre site, with more than 800 detached homes developed on just 100 of those acres. In Dayton, Ohio, the agency created a 107-acre community that included 175 detached homes and a mix of over 600 semidetached homes and row houses, along with schools, shops, a community center and a park.

Notably, the Housing Corporation was not simply committed to offering shelter.

Its architects, planners and engineers aimed to create communities that were not only functional but also livable and beautiful. They drew heavily from Britain’s late-19th century Garden City movement, a planning philosophy that emphasized low-density housing, the integration of open spaces and a balance between built and natural environments.

Importantly, instead of simply creating complexes of apartment units, akin to the public housing projects that most Americans associate with government-funded housing, the agency focused on the construction of single-family and small multifamily residential buildings that workers and their families could eventually own.

This approach reflected a belief by the policymakers that property ownership could strengthen community responsibility and social stability. During the war, the federal government rented these homes to workers at regulated rates designed to be fair, while covering maintenance costs. After the war, the government began selling the homes – often to the tenants living in them – through affordable installment plans that provided a practical path to ownership.

Though the scope of the Housing Corporation’s work was national, each planned community took into account regional growth and local architectural styles. Engineers often built streets that adapted to the natural landscape. They spaced houses apart to maximize light, air and privacy, with landscaped yards. No resident lived far from greenery.

In Quincy, Massachusetts, for example, the agency built a 22-acre neighborhood with 236 homes designed mostly in a Colonial Revival style to serve the nearby Fore River Shipyard. The development was laid out to maximize views, green space and access to the waterfront, while maintaining density through compact street and lot design.

At Mare Island, California, developers located the housing site on a steep hillside near a naval base. Rather than flatten the land, designers worked with the slope, creating winding roads and terraced lots that preserved views and minimized erosion. The result was a 52-acre community with over 200 homes, many of which were designed in the Craftsman style. There was also a school, stores, parks and community centers.

Alongside housing construction, the Housing Corporation invested in critical infrastructure. Engineers installed over 649,000 feet of modern sewer and water systems, ensuring that these new communities set a high standard for sanitation and public health.

Attention to detail extended inside the homes. Architects experimented with efficient interior layouts and space-saving furnishings, including foldaway beds and built-in kitchenettes. Some of these innovations came from private companies that saw the program as a platform to demonstrate new housing technologies.

One company, for example, designed fully furnished studio apartments with furniture that could be rotated or hidden, transforming a space from living room to bedroom to dining room throughout the day.

To manage the large scale of this effort, the agency developed and published a set of planning and design standards − the first of their kind in the United States. These manuals covered everything from block configurations and road widths to lighting fixtures and tree-planting guidelines.

The standards emphasized functionality, aesthetics and long-term livability.

Architects and planners who worked for the Housing Corporation carried these ideas into private practice, academia and housing initiatives. Many of the planning norms still used today, such as street hierarchies, lot setbacks and mixed-use zoning, were first tested in these wartime communities.

And many of the planners involved in experimental New Deal community projects, such as Greenbelt, Maryland, had worked for or alongside Housing Corporation designers and planners. Their influence is apparent in the layout and design of these communities.

With the end of World War I, the political support for federal housing initiatives quickly waned. The Housing Corporation was dissolved by Congress, and many planned projects were never completed. Others were incorporated into existing towns and cities.

Yet, many of the neighborhoods built during this period still exist today, integrated in the fabric of the country’s cities and suburbs. Residents in places such as Aberdeen, Maryland; Bremerton, Washington; Bethlehem, Pennsylvania; Watertown, New York; and New Orleans may not even realize that many of the homes in their communities originated from a bold federal housing experiment.

The Housing Corporation’s efforts, though brief, showed that large-scale public housing could be thoughtfully designed, community oriented and quickly executed. For a short time, in response to extraordinary circumstances, the U.S. government succeeded in building more than just houses. It constructed entire communities, demonstrating that government has a major role and can lead in finding appropriate, innovative solutions to complex challenges.

At a moment when the U.S. once again faces a housing crisis, the legacy of the U.S. Housing Corporation serves as a reminder that bold public action can meet urgent needs.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Eran Ben-Joseph, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Read more: How building more backyard homes, granny flats and in-law suites can help alleviate the housing crisis Colorado takes a new – and likely more effective – approach to the housing crisis Poor and homeless face discrimination under America’s flawed housing voucher system

Eran Ben-Joseph does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.