When a rosary was made for King Henry VIII in 1509, it was hand-carved in intricate detail by a master artisan. By contrast, many of the rosaries around today are made from the same plastic that goes into mass-produced objects such as children’s toys or water bottles.

It doesn’t matter much to the faithful; for devoted Catholics, praying with plastic is just as good as praying with a great work of art.

But it does pose a dilemma for us. As librarians at the University of Dayton’s Marian Library, we help curate a collection of religious artifacts that, depending on how you count it, numbers in the hundreds of thousands. It includes postage stamps, wine labels, books, statues and rosaries. Many of the items are Catholic and have been gifted to the library by charitable individuals looking to do the right thing with a family heirloom or the collection of a recently deceased loved one. Donations could include anything from medieval manuscripts to a car air freshener featuring Our Lady of Guadalupe.

In many cases, donations are welcome. But we struggle with what to do when donations duplicate items we already have, or if the gifted item is not of particular value. And this happens frequently, especially with mass-produced items such as rosaries or cheap plastic statues.

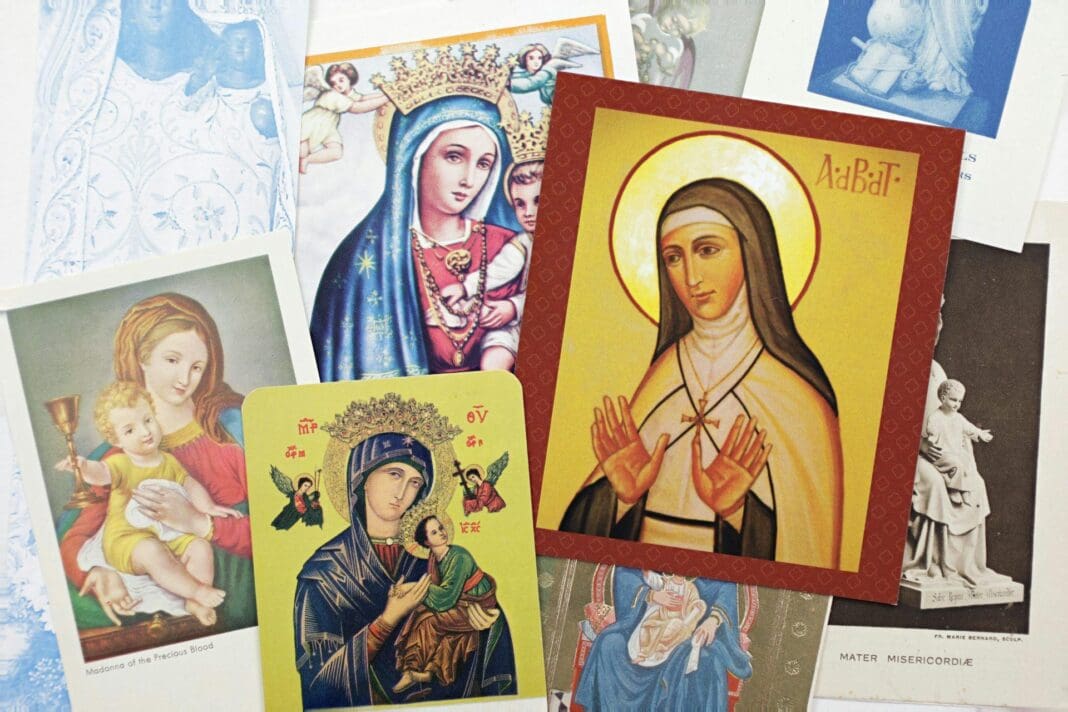

Another example is the holy card. Holy cards or prayer cards are in many ways the religious equivalent to baseball trading cards – they even attract the same type of fanatical collecting. The front usually includes an image of a saint or a religious scene, while the back often has a particular prayer, or the biography of the saint. Early examples of holy cards might be printed on silk or colored by hand. Some can look a bit like the fanciest Valentine’s Day card, with lace borders and room for personal messages.

With advances in printing processes, mass production of holy cards accelerated in the 19th century and continues today, with millions being produced each year. Today, you can purchase 100 new holy cards for less than US$20, and they’re common to pick up at funerals, baptisms or special Masses.

With the mass production and wide distribution of items like holy cards and rosary beads, donations to our collection can multiply quickly. Most months we receive unsolicited gifts of mass-produced materials in the mail. And we are not alone – other libraries, archives and museums likewise receive such gifts.

A widely used guide for running a Catholic church by liturgical scholar G. Thomas Ryan suggests that objects no longer needed should be donated to an archive or museum. But often institutions are short on both staff to process the gifts and space to house them.

Our first step with an unwanted donation is to try to return it to the donor. But that is not always possible when materials appear anonymously or the donor does not want them back.

Someone who has driven several hours to deposit Grandma’s statues unannounced often just wants to drive away unencumbered. So, we look for good homes for items when possible, such as local Catholic schools or parishes.

When regifting isn’t an option, we are presented with a problem. While some unwanted nonreligious donations to libraries might be able to go straight into the trash, that is not an option with many religious objects. As a result, we have needed to investigate the correct way to dispose of religious objects.

According to canon law of the Catholic Church, certain types of especially sacred material, such as holy water and holy oil, must be treated with care and disposed of in specific ways.

The law explains that “sacred objects, set aside for divine worship by dedication or blessing, are to be treated with reverence.” But the law does not explicitly define which objects count as sacred.

Catholic convention is that discarding objects such as statues, rosaries or the palms from Palm Sunday should be by means of respectful burning or burial. But this is not normal practice for most libraries, and the burning of books and artwork has worrying associations with censorship or even war crimes.

But in Catholicism, it would be more scandalous to throw certain religious objects in the trash or sell them for a profit than it would be to burn or bury them, even if no one wants them and they do not fit in our collection.

In addition to protocols around specific types of object, many other Catholic artifacts could be considered sacred depending on how they have been used. This is especially the case if they have been prayed with or blessed.

It can be impossible for us as librarians to know the history of how an object has been used by previous owners – especially if passed to us from a third party. Any holy card, statue or painting could have been blessed as an image and therefore designated as sacred.

In addition to blessings for objects designated for sacred purposes, the Catholic Church literally has a “blessing of anything,” meaning any object could have been blessed by a priest. While this does not necessarily render an object sacred, it does indicate the freedom with which blessings are distributed.

So what are curators supposed to do, given the ongoing mass production, wide distribution and frequent donation of such objects?

The best solution we have found is to remember that intention matters. Our intentions as stewards of these items are good: We communicate up front that not all donations can be accepted, and we try to find new homes for objects that do not belong in the Marian Library – whether by offering items for free to the community or communicating with another library that might be a better fit.

Disposal would be a last resort. To date, we have yet to have a prayerful, respectful fire to destroy duplicate holy cards – but we are not ruling it out.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Kayla Harris, University of Dayton and Sarah B. Cahalan, University of Dayton

Read more: Online Christian pilgrimage: How a virtual tour to Lourdes follows a tradition of innovation The long history of how Jesus came to resemble a white European Pope Francis apologized for the harm done to First Nations peoples, but what does a pope’s apology mean?

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.