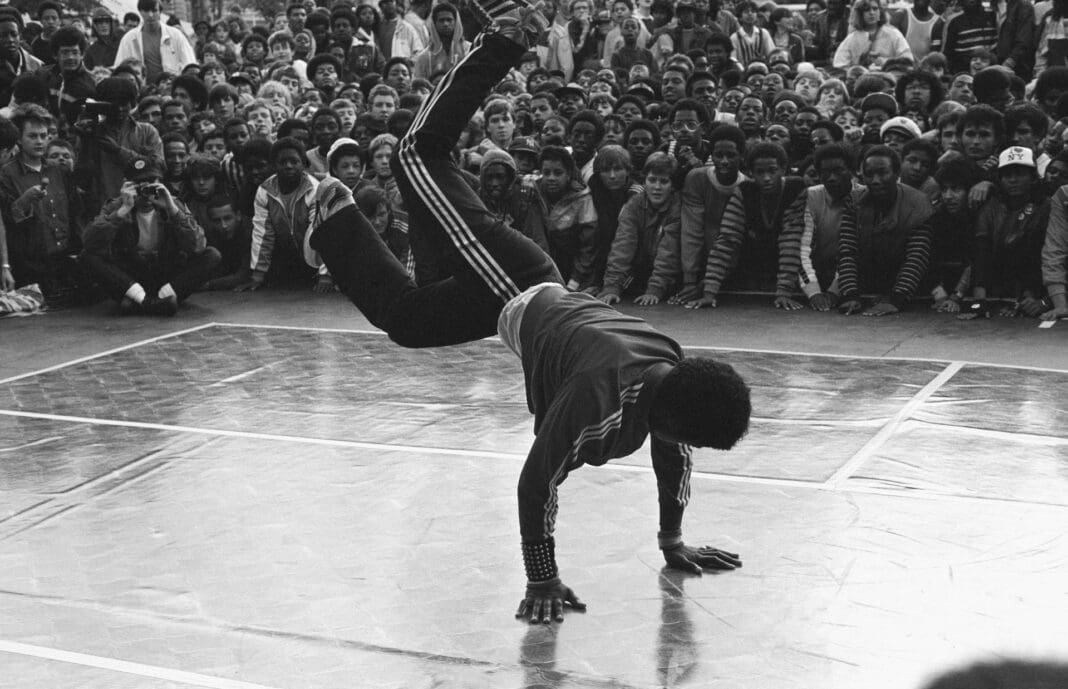

On the evening of Aug. 11, 1973, DJ Kool Herc attended a block party in the South Bronx. Armed with two record players and a mixer, he created an extended percussive break while others rhymed over the beats. Hip-hop was born.

Well, that’s the origin story, although pinpointing the birth of a genre is never going to be an exact science. What is undeniable, though, is that in the 50 years since that event, hip-hop has evolved, grown and influenced nearly every aspect of modern U.S. culture – from dance, theater and literature to visual arts and fashion.

But at the heart will always be the music. Leading up to the landmark anniversary, The Conversation reached out to hip-hop academics – it is a scholarly pursuit, too – to help provide context on how the genre has transformed modern culture, not just in the U.S. but around the world. Below is a selection of the resulting articles, introduced by a key track featured in their writing.

No history of hip-hop would be complete without this 1979 track by The Sugarhill Gang. But along with being an old-school classic, it also kick-started hip-hop’s global expansion.

As Eric Charry, a music professor at Wesleyan University, explained, within months of its being released, versions of “Rapper’s Delight” were being recorded in Brazil, Jamaica, Germany and the Netherlands. Within a year or so, the song’s DNA had spread to Japan and Nigeria.

“It marked the beginning of the globalization of rap music and the broader hip-hop culture in which it is embedded, which includes deejaying, break-dancing and graffiti-tagging,” Charry wrote. But this global spread created what Charry described as a paradox: “The Black American urban culture that birthed rap and hip-hop makes up its very fabric. But so does the core idea of representing one’s own experience and place.”

This led to questions of authenticity that global rappers have contended with ever since, with some digging into their own local culture to square the circle.

Read more:

Despite building on samples and influences from the past, hip-hop as a genre has always pointed forward – as this 1981 track from Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force exemplifies. “Planet rock” also forms part of a tradition in which rappers lean on Afrofuturism – a mix of science fiction, politics and liberating fantasy – to “inform their lyrics and their look,” as Roy Whitaker, a scholar of Africana philosophy of religions at San Diego State University, explained.

“Hip-hop artists influenced by Afrofuturism have long been aware that American society made many Black, Indigenous and other people of color feel different – less than human, or even like aliens – and expressed this through their art. And like socially conscious hip-hop, Afrofuturism has always had a political element,” Whitaker wrote, noting the influence that Afrofuturism pioneers such as musicians Sun Ra and George Clinton and science fiction novelist Octavia Butler had on rap artists from Public Enemy and OutKast to Kendrick Lamar.

“All in all, Afrofuturism counsels marginalized peoples to reassess past wounds and present injustices, while reassuring them that there are possible futures where they can feel they belong,” Whitaker concluded.

Read more:

OK, this is a live performance from the 2001 Grammy Awards show and not a recorded track – though Eminem did release a version of “Stan” featuring British singer Dido a year earlier. But it was a pivotal moment in rap history: Eminem dueting with pop royalty Elton John underscored how hip-hop by the beginning of the 21st century had been accepted by the mainstream music industry.

Moreover, it came at a time when Eminem was deemed deeply controversial because of his use of anti-gay slurs in his tracks. Yet here he was being embraced – both figuratively and physically – by one of the world’s most famous openly gay men. The moment forms part of the hip-hop’s evolution on LGTBQ issues that University of Richmond sociologist Matthew Oware detailed in his article.

He noted that rappers are now having discussions over LGBTQ+ issues and apologizing for hateful speech in their earlier lyrics.

As rap music hits its 50th anniversary, “it is increasingly embracing challenges to – and debates about – homophobia,” Oware wrote. “That is, hip-hop has evolved to the point where anti-gay rhetoric invites condemnation from members of the culture. It is still present in some rap lyrics – as indeed is true of all genres, from pop to country – but hip-hop is changing because of more progressive cultural views and greater LGBTQ+ representation.”

Read more:

While hip-hop’s origins lie in Black American communities, Latino culture is also deeply woven into its story: from pioneers like Kid Frost and Big Pun to Bad Bunny, one of the most-streamed artists making music today.

The genre was “my first love,” wrote Alejandro Nava, a religious studies professor at the University of Arizona. “Hip-hop had its finger on the pulse of Black and brown lives on the frayed edges of the Americas, lives like my father’s and his father’s before him.”

Big Pun, for example – raised in the South Bronx by his Puerto Rican family – alerted the world that “Latins goin’ platinum was destined to come.” Big Pun’s rhymes “spilled off his tongue in torrents of alliteration and assonance, rarely pausing to take a breath or gulp, as if he didn’t require as much oxygen as other humans,” Nava recalled.

From coast to coast, young Latinos “embraced hip-hop as an ingenious instrument of self-expression,” asserting their place in American culture – and often calling for social change.

Read more:

Back in the day, as they still do now, rappers talked about their experiences on the margins of American society. Those social messages connected with Black and immigrant youths throughout Europe who themselves were searching for identity in countries where discrimination remains entrenched.

As a scholar of European studies and identity politics, Armin Langer wrote that modern-day European rappers, particularly Arianna Puello, Black M and Eko Fresh, are challenging outdated European views of citizenship and reshaping public debate on racial and ethnic identity.

Throughout her career, for example, Puello has used her music to confront the racism that she has faced as a Black female migrant in Spain.

In this 2003 track, “Así es la negra,” or “That’s what the Black woman is like,” tells the “ignorant racist,” “You’re going to have to put up with me, If I am born again I want to be what I am now, of the same race, same sex and condition.”

“As migration from African, Caribbean and Middle Eastern countries to Europe continues to increase and European societies discuss questions of identity belonging, it’s my belief that hip-hop will continue to make significant contributions to ongoing public policy debates,” Langer wrote.

Read more:

Of all the elements of hip-hop – which include deejaying, rapping, graffiti-writing and break-dancing – one that seems to get the least attention is the one referred to as hip-hop’s fifth element: “knowledge of self.”

Su'ad Abdul Khabeer, Associate Professor of American Culture at the University of Michigan, expounded on the significance of the phrase. She argued that it became “hip-hop’s consciousness, emphasizing an awareness of injustice and the imperative to address it through both personal and social transformation.”

One of the first rappers to use the phrase in lyrics was Rakim, who mentioned it in his 1987 song “Move the Crowd.” The song is a track on the “Paid in Full” album, which Rolling Stone once listed as No. 61 on its “500 Greatest Albums of All Time.”

In 2005, U.S. rapper Warren “Wawa” Snipe coined the term “dip hop” to describe a burgeoning form of rap music in the Deaf community.

West Virginia University ethnomusicologist Katelyn Best has been following dip hop artists for over a decade. In that time, she’s witnessed dip hop artists achieve mainstream success – including Wawa, whose 2020 song “LOUD” became a top 20 dance track on iTunes.

Dip hop is unique, Best wrote, because “rappers lay down rhymes in sign languages and craft music informed by their experiences within the Deaf community.”

At the same time, the subgenre embodies hip-hop’s broader legacy: speaking – or signing – about experiences of marginalization, while shaking up preexisting notions of what can be considered music.

There is no one way to perform dip hop. Some artists speak and sign simultaneously so their music can be understood by hearing audiences, too. Others collaborate with interpreters, or prerecord vocal tracks that play in the background while they rap in sign language.

“Dip hop, like many styles of music, comes to life through live performance,” Best wrote. “Artists move across the stage with their hands flying through the air as audiences pulse to the rhythm of the blasting bass beat.”

“In the spirit of hip-hop,” Best added, “dip hop rebels both musically and socially against cultural norms, breaking the mold and expanding possibilities for musical artistry.”

Read more:

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. The Conversation is trustworthy news from experts, from an independent nonprofit. Try our free newsletters.

Read more: Why hip-hop needs to be taken more seriously in academic circles The town where hip-hop is healing South Africa’s broken youth