Throughout his 2024 campaign for the presidency, Donald Trump made diplomatic resolution of the Ukraine-Russia war a major priority, suggesting that he could bring peace within “24 hours.” Even before Trump resumed office in January 2025, as president-elect he named envoys and held preliminary discussions with a variety of leaders.

Since Trump returned to the White House, he has talked with Russian leader Vladimir Putin, met twice with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and made frequent public comments on the war.

How does Trump’s mediation effort stack up historically? I’m a scholar of the presidency, and while we don’t yet know the outcome of the Trump-led negotiations, we do know one thing: He’s not conducting them in the ways presidents – including Trump himself – have conducted them in the past.

There are several examples of presidents who attempted to play a mediating role in foreign conflicts.

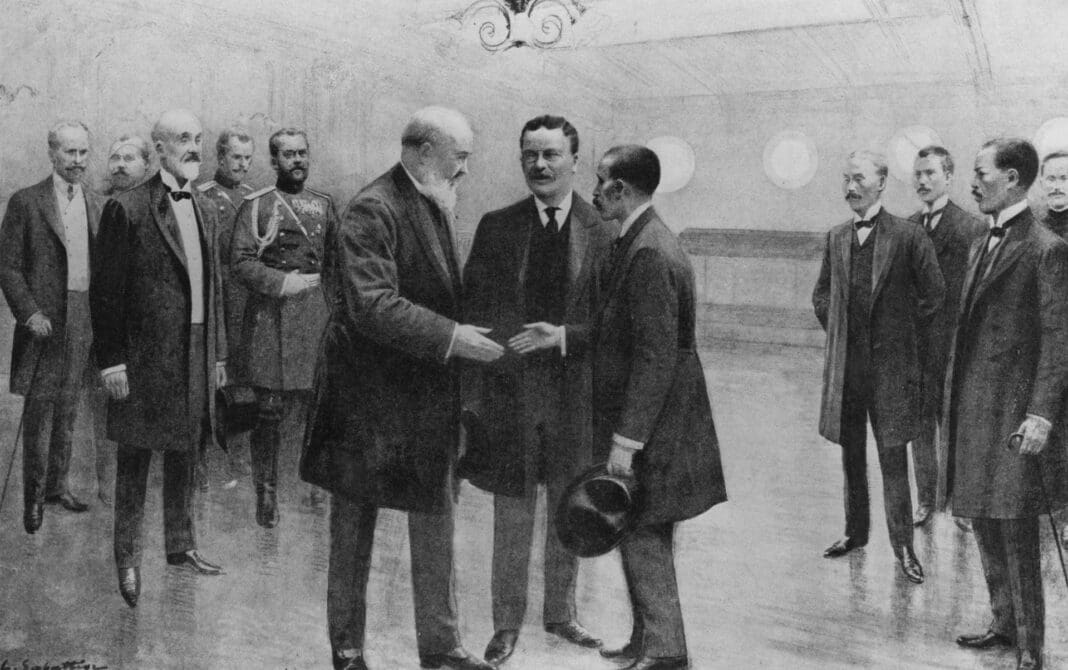

Theodore Roosevelt: Roosevelt won a Nobel Peace Prize for his contributions to ending the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War, fought over control of Manchuria and Sakhalin Island. Roosevelt had been asked to mediate by Japan, and Russia agreed. In many ways, this episode marked the beginning of the role of the U.S. president as a world leader.

Jimmy Carter: Carter’s greatest presidential success arguably came in the Camp David Accords, the framework for peace negotiated in 1978 between Israel and Egypt after decades of conflict. Carter did not win a Nobel Prize for his accomplishment, but Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin did.

Bill Clinton: Clinton made two ambitious attempts to broker peace between old adversaries. One ended in success, the other in failure.

Clinton’s envoy, former U.S. Sen. George Mitchell, mediated an accord between the British government, the Republic of Ireland and the warring factions in Northern Ireland that was signed on Good Friday 1998.

On the other hand, one of Clinton’s greatest frustrations was a failed attempt to arrange peace between Israel and the Palestinians. Clinton blamed the failure on Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat walking away from a deal in 2000. Instead, peace efforts were supplanted by a Palestinian uprising that killed an estimated 1,053 Israeli civilians by early 2005.

Dealing with a third situation – the wars set off by the disintegration of Yugoslavia– the Clinton administration also obtained an agreement over Bosnia in the 1995 Dayton Accords when the parties were sufficiently exhausted.

Donald Trump: In his first presidency, Trump himself brokered the September 2000 Abraham Accords that established formal diplomatic relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco. The accords, brought about largely through negotiations led by Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, had strategic aims of putting greater pressure for peace on the Palestinians and strengthening a common front against Iran. (The Oct. 7, 2023, attacks on Israel by Hamas may have been an attempt to stop subsequent efforts to extend the Abraham Accords to Saudi Arabia.)

Although all of these examples involved presidential leadership and involvement, they did not follow a single model.

Roosevelt never attended the peace negotiations over the Russo-Japanese War in Portsmouth, but he actively offered proposals through intermediaries before and during the conference. The final stages of negotiation were held on his yacht, the Mayflower.

Carter’s breakthrough came when he engaged in intense personal diplomacy at Camp David, where he, Sadat and Begin were sequestered for 13 days. To complete the deal, Carter had to shuffle back and forth between the principals and at one point had to make a frantic appeal to Sadat not to leave.

Clinton’s unsuccessful efforts to broker an agreement between Arafat and a succession of Israeli prime ministers extended over the duration of his two-term presidency and frequently involved personal meetings and exchanges.

On the other hand, Clinton’s involvement in the Northern Ireland resolution did not primarily come in the form of personal diplomacy at the end of the process. Rather, he set the conditions for a settlement earlier when he approved a visa for Irish Republican leader Gerry Adams to enter the U.S., against the wishes of Britain and Clinton’s own advisers.

When Clinton went to Belfast for a Christmas tree lighting in 1995, he brought together Catholic leaders committed to the unification of Ireland and Protestant leaders loyal to Britain. First lady Hillary Clinton also contributed by meeting with Irish women’s organizations on both sides.

In contrast, in the Dayton process Clinton was later portrayed by chief negotiator Richard Holbrooke as essentially disengaged.

Although each mediation effort was unique, there were some commonalities.

First, where sensitive issues of land possession were involved, many of the negotiations benefited from privacy in the process.

Second, successful mediations came most often when the U.S. was neutral, such as in the Portsmouth negotiations, or friendly toward both parties to some degree, such as with the Camp David, Good Friday and Abraham negotiations. Dayton was the exception in that the U.S. had become quite hostile toward the Serbs.

In Ukraine, Trump is attempting to mediate a conflict in which, until now, the U.S. has been firmly and materially supportive of one side against the other. And he is attempting to do it by publicly making, so far, proposals that were destined to be toxic to the Ukrainian public.

Trump appears to be violating the first rule above – no public negotiations over land – in order to chase compliance with the second, which is no mediation without neutrality. By, among other things, publicly offering proposals that the Ukrainians see as one-sided against them, Trump has largely erased the image of the U.S. as pro-Ukraine.

This is a highly controversial and risky strategy that has damaged relations with U.S. allies and cost the U.S. moral capital in pursuit of an uncertain peace.

Whatever success Trump ultimately achieves, it is little surprise that the effort, which has been pursued over a period of six months so far, has been more difficult than he anticipated.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Andrew E. Busch, University of Tennessee

Read more: Lessons in realpolitik from Nixon and Kissinger: Ideals go only so far in ending conflict in places like Ukraine Saudi Arabia’s role as Ukraine war mediator advances Gulf nation’s diplomatic rehabilitation − and boosts its chances of a seat at the table should Iran-US talks resume From certain war to uncertain peace: Northern Ireland’s Good Friday Agreement turns 20

Andrew E. Busch does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.