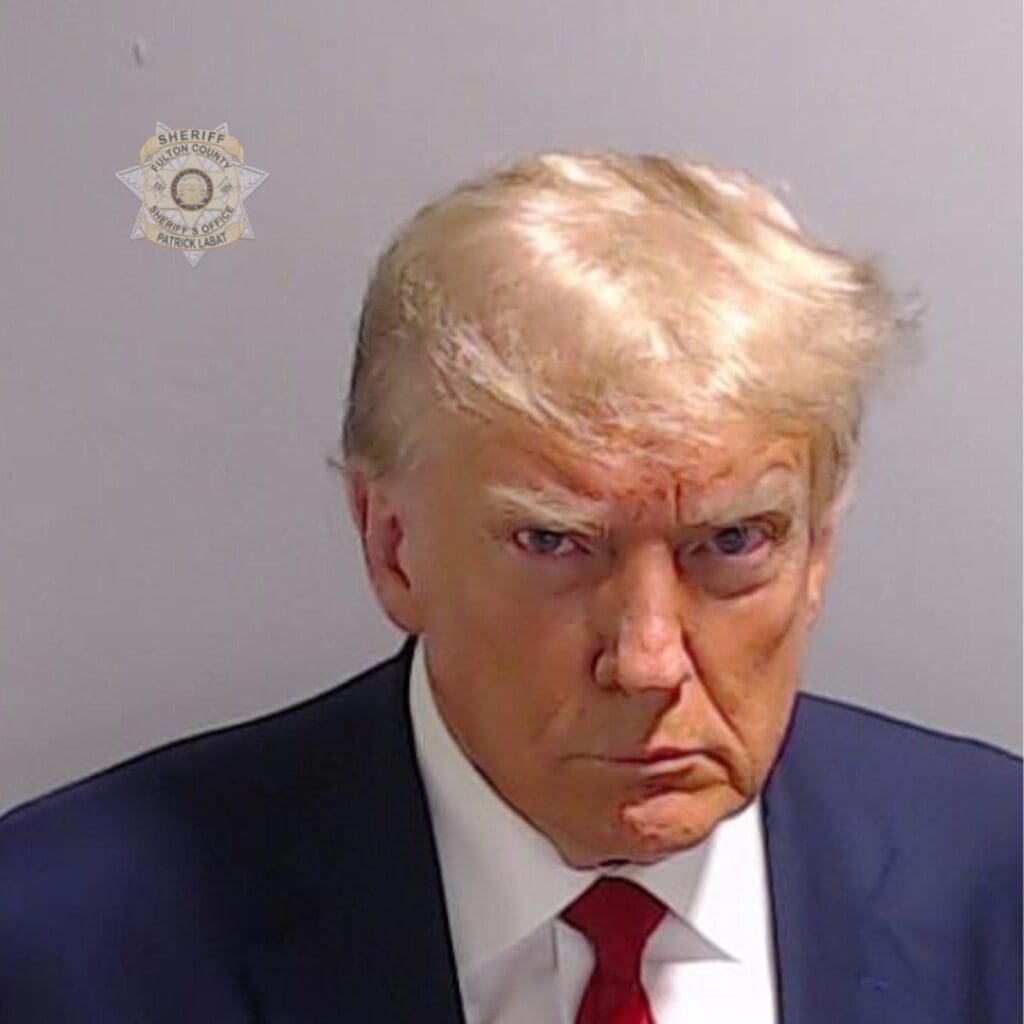

For several days, former President Donald Trump and his 18 co-defendants in a Georgia election interference case trickled into the Fulton County Jail in Atlanta to surrender for arrest, fingerprinting and mugshots before the noon Aug. 25, 2023, deadline. Charged in the same alleged conspiracy to overturn results in Georgia’s 2020 presidential election, the defendants did not draw the same bail agreements or amounts.

Trump’s bail was set at US$200,000, while his former attorney Rudy Giuliani’s bail was set at $150,000. Meanwhile, attorneys John Eastman, Kenneth Chesebro, Jenna Ellis and Sidney Powell each had bail set at $100,000. Bail for other co-defendants ranged from $10,000 to $75,000.

The Conversation asked Megan T. Stevenson, a University of Virginia law professor who researches bail, to answer questions about the American bail system and how the bail amounts in the Georgia election interference case reflect that system.

Cash bail is when the defendant must pay money before being released from jail after arrest. The money can come from the defendant’s savings, from a friend or family member, or be borrowed from a bail bondsman. The words bail and bond are often used interchangeably.

The idea behind cash bail is that it provides a financial incentive to deter misconduct. If a defendant flees or otherwise misbehaves, they forfeit their bail amount.

After someone is arrested, they are seen by a judge or magistrate who sets bail. The bail hearing is usually exceedingly short – a few minutes at most. Sometimes, the hearings happen by video conference.

Most defendants do not have defense counsel at the time of the bail hearing, but if they do, the defense counsel can argue for lenient bail amounts and conditions.

While bail laws vary from state to state, bail is usually supposed to be set at the minimal amount of money that will ensure the defendant appears in court and doesn’t violate court orders. For instance, one of the conditions of Trump’s bail is that he cannot intimidate witnesses, co-defendants or other people – including on social media. If Trump violates this condition, he is at risk of having his bond revoked and being placed in jail.

Bail has been a part of the American criminal justice system since Colonial times. Originally, when a criminal defendant was released on bail, it meant they were released into the supervision of someone who had vouched for them. The defendant would be required to pay a certain amount of money if they failed to subsequently appear in court. But no one needed to pay any money up front. Over time, that has changed. Now, most defendants are expected to pay cash bail before they are released, and a surety – a person who vouchers for the defendant and promises to supervise them – is generally not required.

In the U.S., people are presumed innocent until proved guilty in court. Being jailed prior to trial is supposed to be a “carefully limited exception” as established by Supreme Court precedent.

But that reflects theory better than practice. Approximately 20% of the imprisoned population in the U.S. consists of people awaiting trial.

For reference, there are more people detained pretrial than are serving time due to a drug sentence. And almost all of those detained had cash bail set and would have been released if they could afford it.

Some detained people are facing very serious charges and had very high bail. But many are detained on relatively low bail amounts that are simply beyond reach for the poor to pay.

Theoretically, the ability to pay bail is supposed to be taken into account, but judges frequently don’t. The result is that people end up behind bars before trial simply because they are accused of a crime and they are poor, which is both a violation of equal protection and a waste of taxpayer resources.

The bail reform movement is trying to ensure that the only people detained before trial are people who pose a specific threat of serious crime if they are released. Illinois, for example, eliminated its cash bail system, making all defendants eligible for release before trial. In other jurisdictions, nonprofit bail funds pay bail for the poor, with the goal of ensuring that nobody is jailed due to inability to pay.

Yes. Trump and his co-defendants have been charged in a conspiracy. But conspiracy law is very sweeping and can range from central players in the crime to those with very minor roles. When setting bail, judges take into account the seriousness of the alleged criminal activity, the criminal record and any other information that pertains to the likelihood that the defendant will flee, intimidate witnesses or commit a new crime. Given the wide variety of roles Trump and his co-defendants allegedly played, as well as these other varying circumstances, it’s not surprising that their bail would differ.

Studies show that racial bias and racial disparities in bail exist, and they arise from various sources. First, a defendant’s criminal record plays a big role in the bail amount. If defendants from disadvantaged groups are more likely to be arrested than others who have committed the same crime, then they will have longer criminal records and will get higher bail amounts. For instance, numerous studies show that Black people use and sell drugs at similar rates to white people, but are much more likely to be arrested and convicted for drug crimes. So, Black people in the criminal justice system often have longer criminal records than white people in the system.

Also, a judge’s beliefs about the likelihood that someone will commit a crime in the future can be influenced by stereotypes about race and criminality. These stereotypes can lead a judge to set bail higher for Black defendants who pose the same risk level as white defendants.

Finally, poor people will be less able to afford a certain bail amount than those with greater wealth. And since poverty is strongly correlated with race, Black and Hispanic defendants are often detained at disproportionate rates.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. If you found it interesting, you could subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Read more: Fulton County charges Donald Trump with racketeering, other felonies – a Georgia election law expert explains 5 key things to know Black female prosecutors like Fani Willis face the unequal burden of both racist and sexist attacks

Megan T. Stevenson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.