All living organisms age. People have long sought ways to slow, halt or reverse this process, which is commonly associated with declining mental and physical health. One area researchers are probing is the role that sensory perception – such as sight, smell, sound, taste and touch – plays on health and life span.

While you may typically think of your senses as what you use to gather information about your surroundings, recent work has demonstrated that environmental cues themselves can affect physiology and aging. Your body regulates itself to match the conditions it finds itself in. The nervous system is poised as a central player in mediating the effects of sensory perception. It stores and integrates incoming information from the environment and interprets and disseminates information across different tissues.

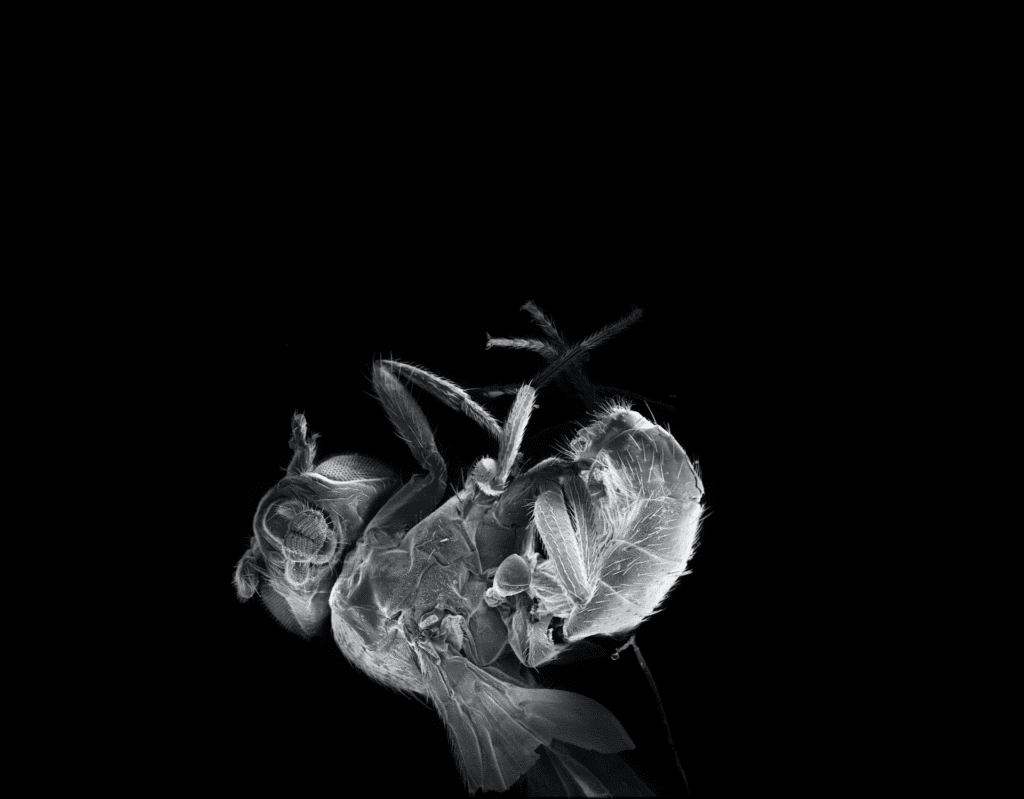

I have used fruit flies, specifically Drosophila melanogaster, for more than 15 years to better understand how sensory perception affects aging. Recently my work has focused on the role the brain plays in aging, looking at how death perception, or when fruit flies perceive other dead fruit flies, affects their life span. My colleagues and I have shown that when fruit flies see, and to a lesser extent smell, an excess of dead flies in their environment, they avoid other flies and undergo significant physiological changes, including rapid decreases in stored fat, decreased resistence to starvation and shortened life span. While it is currently unknown whether these changes are evolutionarily advantageous, we speculate that it could be, because of the stressful environment that the living flies find themselves in.

In our newly published research, my colleagues and I identified the neural circuits and signaling processes behind the physiological effects, including rapid aging, that occur when Drosophila encounter their dead. Because other animals also experience physiological effects in the presence of their dead, identifying how this process works in fruit flies could shed light on how it operates in other species, including in people.

Using genetic tools that detect which neurons are likely activated when live flies are exposed to dead flies, we identified a handful of neurons in the Drosophila brain called R2/R4 neurons that act as a rheostat for aging. These neurons are the center of sensory information processing and motor coordination in fruit fly brains. Inhibiting or activating them changed the aging rate of the flies, suggesting that these neurons alter fly life span in response to perceiving dead flies.

Next, we wanted to identify which molecules produced by R2/R4 neurons were responsible for spurring aging after flies witnessed other dead flies. Since components of a signaling pathway involved in glucose regulation have long been associated with aging, we focused on a protein called Foxo that is associated with the pathway.

We discovered that flies without Foxo had similar life spans whether or not there were dead flies present. We saw the same result when we decreased the amount of Foxo in R2/R4 neurons. These findings suggest that Foxo in R2/R4 neurons plays a key role in changing the life span of living flies.

We also discovered that other components of the signaling pathway involved in glucose regulation, called Drosophila insulin-like peptides, or dilps, mediate the effect of death perception on life span. Because these molecules appeared after changes in R2/R4 neuron activity, this suggests that they do not directly affect Foxo in these neurons. They likely work on other tissues.

There are many examples of how sensory perception affects aging in animals, suggesting that it is a phenomenon that occurs across species.

For example, manipulating specific subsets of sensory neurons in the worm Caenorhabditis elegans can either shorten or extend its life span. Genetically manipulating fruit flies to lose their sense of smell makes them live longer. Furthermore, environmental cues that indicate the presence of food, water, danger and potential mates all significantly influence physiology and longevity.

Manipulating the sensory system can affect aging even in mammals. For example, losing a specific pain receptor can significantly extend the life span of mice.

The effects of seeing dead fruit flies on the physiology of fruit flies resemble changes seen in other species. For instance, social insects like ants and honeybees carry their dead away from the colony in a behavior called necrophoresis. Nonhuman primates also experience increased glucocorticoid levels when a relative dies. This suggests that the processes that mediate these changes have similarities across species. My research team has previously shown that the effects of death perception in Drosophila involved chemical compounds and neural signaling that have been conserved throughout evolution.

The specific cues that lead to changes in the life spans of worms, flies and mice are likely species-specific. But the fact that they are all affected by changes in sensory input suggests that the molecular mechanisms driving age-related changes may be shared by all, including people.

Altogether, our work provides insight into the neural underpinnings of how the senses affect aging. While translating these findings to humans is clearly speculative, we hope that more research can eventually help researchers better understand the physiological and psychological effects of people who routinely witness death, such as soldiers and first responders.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. If you found it interesting, you could subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

Read more: Are you a rapid ager? Biological age is a better health indicator than the number of years you’ve lived, but it’s tricky to measure Genetic GPS system of animal development explains why limbs grow from torsos and not heads

Christi Gendron does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.