One group of American voters is being largely ignored in the closely watched polling leading up to the Nov. 5 elections: U.S. citizens living abroad, whether as civilians or as members of the military. We know from governmental data that the number of ballots cast by overseas Americans has been greater than the margin of victory in races in the past – and may be again in 2024.

But that one potentially crucial group of American voters – U.S. citizens living abroad – does not get much attention, from pollsters or campaigns.

We are scholars of political science whose research shows that overseas voters can make a difference in elections – and that there is potential for campaigns to mobilize these voters, despite a more complex process of voting than for domestic voters.

Though there is not an exact count of American citizens living abroad, we do know they number in the millions. Estimates from the Federal Voter Assistance Program and the Association of Americans Resident Overseas placed this number between 4.4 million and 5.3 million in 2023.

But those are likely undercounts. It’s almost impossible to account fully for dual citizens, naturalized U.S. citizens who have returned to the country of their birth or people who split their time between the U.S. and other countries.

Research that we and others have conducted indicates that Mexico and Canada are home to the largest numbers of Americans outside the U.S., followed by the U.K., France, Israel and Germany. The three most common reasons Americans move abroad are family connections, employment and quality of life, although there are others.

Overseas Americans tend to be highly educated: More than three-quarters have a college degree, double the percentage within the U.S. Most overseas Americans do not move from country to country but rather stay in one country, often for a decade or more. But our surveys have found they remain interested in U.S. politics – not least because they pay U.S. income taxes, whether they work for a U.S. or foreign employer. IRS data shows that the vast majority are not ultra-wealthy.

Military members and U.S. citizens living abroad have had the right to vote in federal elections since 1976. This right was further consolidated in the 1986 Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act, while the right for Americans living abroad to vote in local and state elections depends on state law.

Some people have recently expressed concern that overseas voting could be used to cast fraudulent ballots, but there is no evidence of illegal voting by noncitizens abroad.

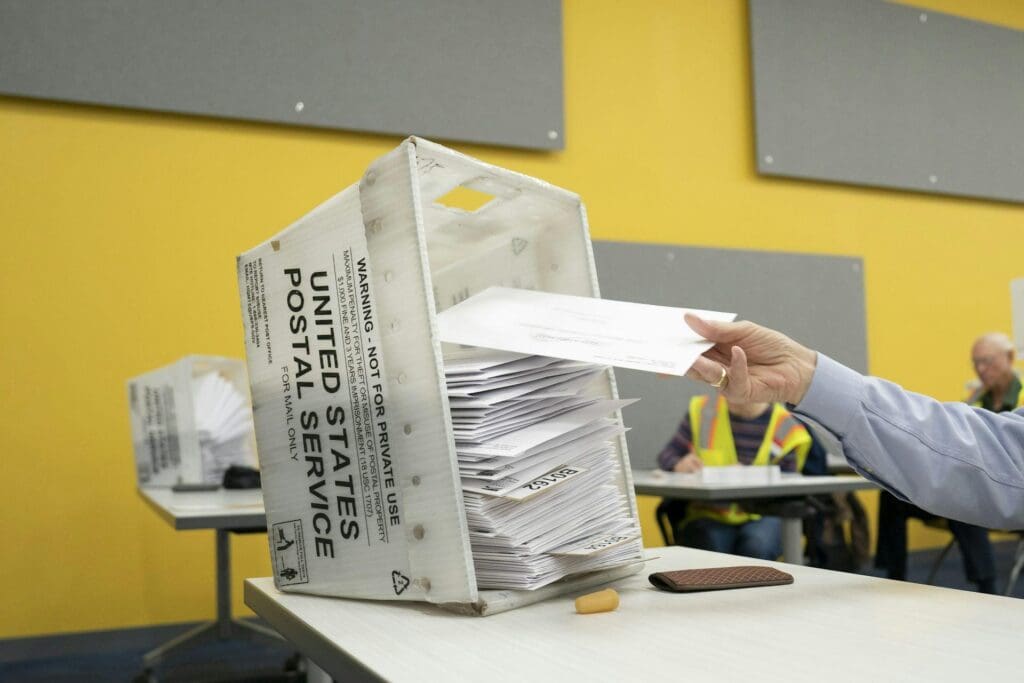

Overseas voters’ absentee ballot requests and their returned ballots are carefully scrutinized by local officials in the state where they last lived in the U.S., making abuse very unlikely. But it is complex for overseas voters to vote: The paperwork is complicated, and there is comparatively little outreach from political parties and candidates.

In 2020, the Federal Voting Assistance Program, which is supposed to help overseas voters exercise their voting rights, estimated that just shy of 8% of eligible American voters overseas cast ballots in that year’s presidential election. Using program numbers to calculate a percentage another way finds that no more than 20% of overseas Americans cast ballots in the 2020 election.

That’s far lower than the 67% national turnout rate that year.

Federal law requires local election officials in the U.S. to mail absentee ballots 45 days before an election to overseas Americans who request them. Poor mail service in the U.S. and elsewhere can mean that voters don’t always get the ballots in time, and the ballots mailed back to election officials face similar delays.

Some states allow voters to receive or return their ballots electronically, which is faster; an overseas voter casting a ballot in Massachusetts can request a ballot, receive a blank ballot and return it all by email, while an overseas voter from Pennsylvania must return it by mail or courier, following exact procedures for enclosing their ballot in multiple envelopes.

In 2023, the Federal Voting Assistance Program estimated that as many as 150,000 U.S. citizens overseas did not cast ballots in the 2022 elections because of administrative hurdles, such as slow or irregular mail service and difficulties in communicating procedural changes to prospective voters abroad.

Another possible reason Americans abroad don’t vote is that they have lost interest in U.S. politics. But our own research, and the work of others, finds that not to be true.

Even given the logistical challenges, U.S. citizens living in Canada, as one example, have very similar levels of interest in American politics compared with citizens back home.

During the 2020 and 2022 campaign seasons, two of us surveyed American citizens who had moved north of the border. In 2020, 55% indicated they were very interested in American politics, as did 44% in the midterm year of 2022. This is comparable with levels of attention to politics within the U.S. during those campaigns, as gauged by the Cooperative Election Study.

So although Americans in Canada indicated interest levels as high as those in the U.S. during the past two national election cycles, the vast majority of them did not cast a vote. Administrative barriers play a role, but they’re not enough to explain such low turnout among citizens overseas.

Another key factor driving low turnout from abroad is a lack of communication from campaigns and parties. Research demonstrates that contacts by campaigns and parties significantly increase a person’s likelihood of voting.

In the U.S., parties and campaign organizations can help streamline the voter registration process, reinforce the stakes of an election and bolster a sense of camaraderie among citizens.

U.S. citizens living abroad are unlikely to hear from campaigns, even in nearby Canada. When asked in 2020 or 2022 whether they had been contacted by American political campaigns, most potential voters in the U.S. had. But our surveys of Americans living in Canada show less than one-third reported contact from parties or candidates.

Because overseas citizens vote in their last state of residence in the U.S. but are not physically resident there, campaigns find it harder to identify them as swing-state residents or members of favorable demographic groups.

Overall, Americans living overseas are as eligible to vote as citizens in the U.S. They are as attentive to politics as Americans living in the U.S. On the other hand, they face major administrative hurdles and are generally not contacted by American parties or campaigns.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Amanda Klekowski von Koppenfels, University of Kent; James A. McCann, Purdue University, and Ronald Rapoport, William & Mary

Read more: 4 ways AI can be used and abused in the 2024 election, from deepfakes to foreign interference ‘Suicide for democracy.’ What is ‘bothsidesism’ – and how is it different from journalistic objectivity? Americans living and serving overseas could tilt the 2020 election – if only they voted

James A. McCann has received support for his research on migration from Purdue University, the US Fulbright Program, the Russell Sage Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Amanda Klekowski von Koppenfels and Ronald Rapoport do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.