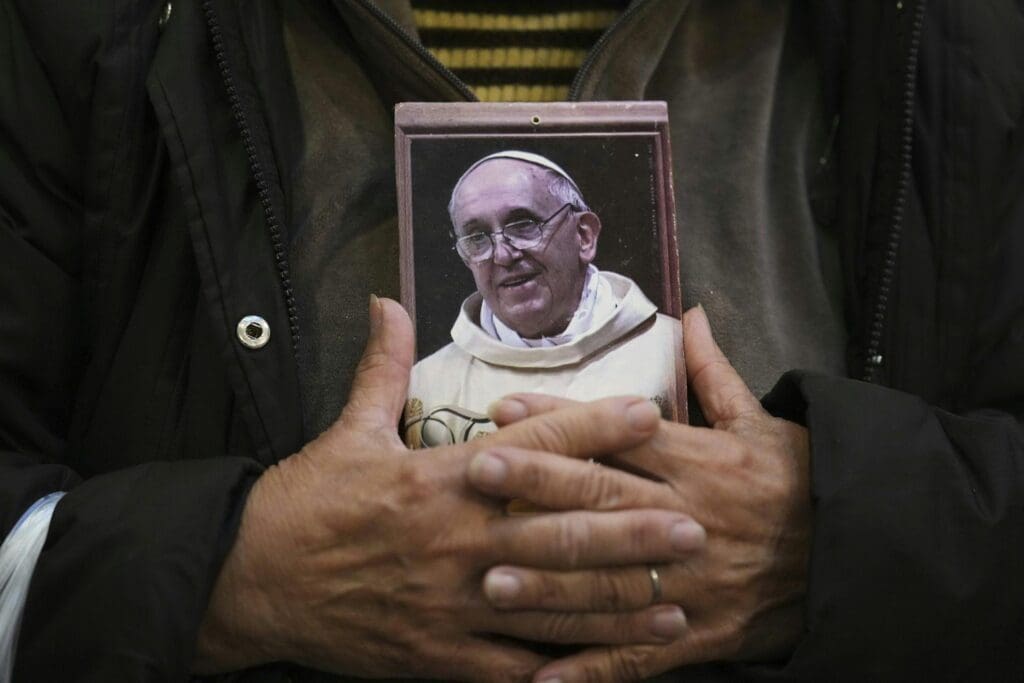

Pope Francis, whose papacy blended tradition with pushes for inclusion and reform, died on April, 21, 2025 – Easter Monday – at the age of 88.

Here we spotlight five stories from The Conversation’s archive about his roots, faith, leadership and legacy.

Jorge Mario Bergoglio became a pope of many firsts: the first modern pope from outside Europe, the first whose papal name honors St. Francis of Assisi, and the first Jesuit – a Catholic religious order founded in the 16th century.

Those Jesuit roots shed light on Pope Francis’ approach to some of the world’s most pressing problems, argues Timothy Gabrielli, a theologian at the University of Dayton.

Gabrielli highlights the Jesuits’ “Spiritual Exercises,” which prompt Catholics to deepen their relationship with God and carefully discern how to respond to problems. He argues that this spiritual pattern of looking beyond “presenting problems” to the deeper roots comes through in Francis’ writings, shaping the pope’s response to everything from climate change and inequality to clerical sex abuse.

Read more:

Early on in his papacy, Francis famously told an interviewer, “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?” Over the years, he has repeatedly called on Catholics to love LGBTQ+ people and spoken against laws that target them.

But “Francis’ inclusiveness is not actually radical,” explains Steven Millies, a scholar at the Catholic Theological Union. “His remarks generally correspond to what the church teaches and calls on Catholics to do,” without changing doctrine – such as that marriage is only between a man and a woman.

Rather, Francis’ comments “express what the Catholic Church says about human dignity,” Millies writes. “Francis is calling on Catholics to take note that they should be concerned about justice for all people.”

Read more:

At times, Francis did something that was once unthinkable for a pope: He apologized.

He was not the first pontiff to do so, however. Pope John Paul II declared a sweeping “Day of Pardon” in 2000, asking forgiveness for the church’s sins, and Pope Benedict XVI apologized to victims of sexual abuse. During Francis’ papacy, he acknowledged the church’s historic role in Canada’s residential school system for Indigenous children and apologized for abuses in the system.

But what does it mean for a pope to say, “I’m sorry”?

Annie Selak, a theologian at Georgetown University, unpacks the history and significance of papal apologies, which can speak for the entire church, past and present. Often, she notes, statements skirt an actual admission of wrongdoing.

Still, apologies “do say something important,” Selak writes. A pope “apologizes both to the church and on behalf of the church to the world. These apologies are necessary starting points on the path to forgiveness and healing.”

Read more:

Many popes convene meetings of the Synod of Bishops to advise the Vatican on church governance. But under Francis, these gatherings took on special meaning.

The Synod on Synodality was a multiyear, worldwide conversation where Catholics could share concerns and challenges with local church leaders, informing the topics synod participants would eventually discuss in Rome. What’s more, the synod’s voting members included not only bishops but lay Catholics – a first for the church.

The process “pictures the Catholic Church not as a top-down hierarchy but rather as an open conversation,” writes University of Dayton religious studies scholar Daniel Speed Thompson – one in which everyone in the church has a voice and listens to others’ voices.

Read more:

In 2024, University of Notre Dame professor David Lantigua had a cup of maté tea with some “porteños,” as people from Buenos Aires are known. They shared a surprising take on the Argentine pope: “a theologian of the tango.”

Francis does love the dance – in 2014, thousands of Catholics tangoed in St. Peter’s Square to honor his birthday. But there’s more to it, Lantigua explains. Francis’ vision for the church was “based on relationships of trust and solidarity,” like a pair of dance partners. And part of his task as pope was to “tango” with all the world’s Catholics, carefully navigating culture wars and an increasingly diverse church.

Francis was “less interested in ivory tower theology than the faith of people on the streets,” where Argentina’s beloved dance was born.

Read more:

This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.