Every year, China’s minister of foreign affairs embarks on what has now become a customary odyssey across Africa. The tradition began in the late 1980s and sees Beijing’s top diplomat visit several African nations to reaffirm ties. The most recent visit, by Foreign Minister Wang Yi, took place in mid-January 2025 and included stops in Namibia, the Republic of the Congo, Chad and Nigeria.

For over two decades, China’s burgeoning influence in Africa was symbolized by grand displays of infrastructural might. From Nairobi’s gleaming towers to expansive ports dotting the continent’s shorelines, China’s investments on the continent have surged, reaching over US$700 billion by 2023 under the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s massive global infrastructure development strategy.

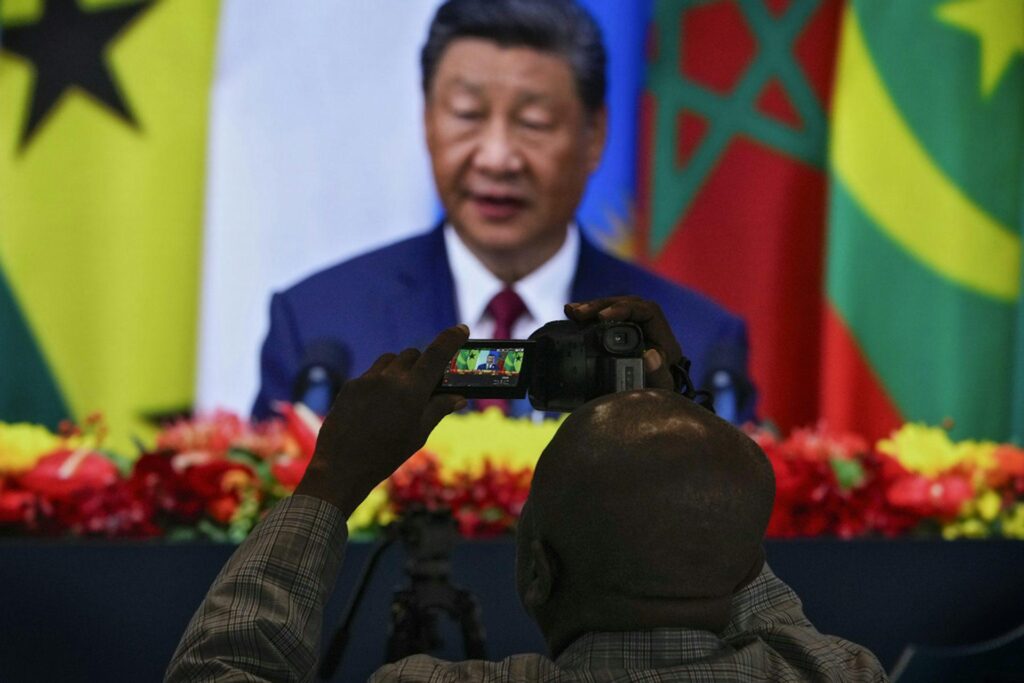

But in recent years, Beijing has sought to expand beyond roads and skyscrapers and has made a play for the hearts and minds of African people. With a deft mix of persuasion, power and money, Beijing has turned to African media as a potential conduit for its geopolitical ambitions.

Partnering with local outlets and journalist-training initiatives, China has expanded China’s media footprint in Africa. Its purpose? To change perceptions and anchor the idea of Beijing as a provider of resources and assistance, and a model for development and governance.

The ploy appears to be paying dividends, with evidence of sections of the media giving favorable coverage to China. But as someone researching the reach of China’s influence overseas, I am beginning to see a nascent backlash against pro-Beijing reporting in countries across the continent.

China’s approach to Africa rests mainly on its use of “soft power,” manifested through things like the media and cultural programs. Beijing presents this as “win-win cooperation” – a quintessential Chinese diplomatic phrase mixing collaboration with cultural diplomacy.

Key to China’s media approach in Africa are two institutions: the China Global Television Network (CGTN) Africa and Xinhua News Agency.

CGTN Africa, which was set up in 2012, offers a Chinese perspective on African news. The network produces content in multiple languages, including English, French and Swahili, and its coverage routinely portrays Beijing as a constructive partner, reporting on infrastructure projects, trade agreements and cultural initiatives. Moreover, Xinhua News Agency, China’s state news agency, now boasts 37 bureaus on the continent.

By contrast, Western media presence in Africa remains comparatively limited. The BBC, long embedded due to the United Kingdom’s colonial legacy, still maintains a large footprint among foreign outlets, but its influence is largely historical rather than expanding. And as Western media influence in Africa has plateaued, China’s state-backed media has grown exponentially. This expansion is especially evident in the digital domain. On Facebook, for example, CGTN Africa commands a staggering 4.5 million followers, vastly outpacing CNN Africa, which has 1.2 million — a stark indicator of China’s growing soft power reach.

China’s zero-tariff trade policy with 33 African countries showcases how it uses economic policies to mold perceptions. And state-backed media outlets like CGTN Africa and Xinhua are central to highlighting such projects and pushing an image of China as a benevolent partner.

Stories of an “all-weather” or steadfast China-Africa partnership are broadcast widely, and the coverage frequently depicts the grand nature of Chinese infrastructure projects. Amid this glowing coverage, the labor disputes, environmental devastation or debt traps associated with some Chinese-built infrastructure are less likely to make headlines.

Questions of media veracity notwithstanding, China’s strategy is bearing fruit. A Gallup poll from April 2024 showed China’s approval ratings climbing in Africa as U.S. ratings dipped. Afrobarometer, a pan-African research organization, further reports that public opinion of China in many African countries is positively glowing, an apparent validation of China’s discourse engineering.

Further, studies have shown that pro-Beijing media influences perceptions. A 2023 survey of Zimbabweans found that those who were exposed to Chinese media were more likely to have a positive view of Beijing’s economic activities in the country.

The effectiveness of China’s media strategy becomes especially apparent in the integration of local media. Through content-sharing agreements, African outlets have disseminated Beijing’s editorial line and stories from Chinese state media, often without the due diligence of journalistic skepticism.

Meanwhile, StarTimes, a Chinese media company, delivers a steady stream of curated depictions of translated Chinese movies, TV shows and documentaries across 30 countries in Africa.

But China is not merely pushing its viewpoint through African channels. It’s also taking a lead role in training African journalists, thousands of whom have been lured by all-expenses-paid trips to China under the guise of “professional development.” On such junkets, they receive training that critics say obscures the distinction between skill-building and propaganda, presenting them with perspectives conforming to Beijing’s line.

Ethiopia exemplifies how China’s infrastructure investments and media influence have fostered a largely favorable perception of Beijing. State media outlets, often staffed by journalists trained in Chinese-run programs, consistently frame China’s role as one of selfless partnership. Coverage of projects like the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway line highlights the benefits, while omitting reports on the substandard labor conditions tied to such projects — an approach reflective of Ethiopia’s media landscape, where state-run outlets prioritize economic development narratives and rely heavily on Xinhua as a primary news source.

In Angola, Chinese oil companies extract considerable resources and channel billions into infrastructure projects. The local media, again regularly staffed by journalists who have accepted invitations to visit China, often portray Sino-Angolan relations in glowing terms. Allegations of corruption, the displacement of local communities and environmental degradation are relegated to side notes in the name of common development.

Despite all of the Chinese influence, media perspectives in Africa are far from uniformly pro-Beijing.

In Kenya, voices of dissent are beginning to rise, and media professionals immune to Beijing’s allure are probing the true costs of Chinese financial undertakings. In South Africa, media watchdogs are sounding alarms, pointing to a gradual attrition of press freedoms that come packaged with promises of growth and prosperity. In Ghana, anxiety about Chinese media influence permeates more than the journalism sector, as officials have raised concerns about the implications of Chinese media cooperation agreements. Wariness in Ghana became especially apparent when local journalists started reporting that Chinese-produced content was being prioritized over domestic stories in state media.

Beneath the surface of China’s well-publicized projects and media offerings, and the African countries or organizations that embrace Beijing’s line, a significant countervailing force exists that challenges uncritical representations and pursues rigorous journalism.

Yet as CGTN Africa and Xinhua become entrenched in African media ecosystems, a pertinent question comes to the forefront: Will Africa’s journalists and press be able to uphold their impartiality and retain intellectual independence?

As China continues to make strategic inroads in Africa, it’s a fair question.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Mitchell Gallagher, Wayne State University

Read more: We asked 1,000 Zimbabweans what they think of China’s influence on their country − only 37% viewed it favorably Growth of autocracies will expand Chinese global influence via Belt and Road Initiative as it enters second decade Trump tariffs: there may be silver linings in the trade war storm clouds

Mitchell Gallagher does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.